James Powell & Sons, better known as Whitefriars Glass, was the longest-running glass house in Britain and started in the mid-18th century. The Old Glass House in Tudor Street dates back to 1740 but records date back to a small glassworks off Fleet Street in 1720.

Whitefriars Glass History: James Powell & Sons

James Powell was a wine merchant and entrepreneur and a relative of the famous Scout Movement founder, Baden Powell. He bought the factory in 1834 for his three sons, who had no experience in glassmaking.

They, by necessity, found their feet and began incorporating and improving on the new manufacturing processes and technologies emerging from the (by then 100-year-old) Industrial Revolution.

One of their main products was mass-produced decorative quarry glass, which was moulded, printed with black detailing, and stained yellow rather than hand-cut and painted. This was a lot cheaper to produce than stained glass and was often used in churches (later to be replaced with stained glass). In the hidden alcoves of Victorian churches, you can often still see examples of this quarry glass.

Due to the boom in Victorian church buildings, they did very well and became leaders in the field. They were great innovators, and they patented many new manufacturing processes. This success led to them working closely with some of the leading architects and designers of the day, including Philip Webb who designed a range of glass vessels for William Morris that was made by Whitefriars.

Thanks to their work with William Morris, they were commissioned to manufacture table glass for his revolutionary Red House. Inspired by this, they began producing a range of glassware in the mid-19th century.

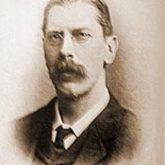

In 1875, Harry James Powell, the founder’s grandson, joined the factory and brought a more scientific approach to glassmaking.

In 1875, Harry James Powell, the founder’s grandson, joined the factory and brought a more scientific approach to glassmaking.

He was a chemistry graduate from Oxford and discovered many new innovations and glass colours.

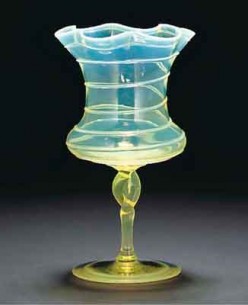

He was responsible for the development of opalescent glass, heat-resistant laboratory glass, x-ray tubes, and lightbulbs.

Darlings of the Victorian Age

They became darlings of late Victorian fashion and created tableware inspired by ancient glass or copied from the great paintings hung in museums and art galleries around the world. Harry was a socialite and follower of Ruskin (the famous social thinker and art critic who thought cut glass was “barbarous”) and was involved in many movements.

The designs the factory produced also moved with the times, and around the turn of the century, the latest art movement was the Art Nouveau style. This was a time when the factory produced some of its most beautiful glassware.

In 1919, the company changed its name from James Powell & Sons to Powell & Sons (Whitefriars) Ltd., and in 1923, they opened their purpose-built facility in Wealdstone, near Harrow. They took burning coal from one of the furnaces in Fleet Street in a metal brazier and took it to the new factory to light the furnaces for the first time.

The Powells were heavily influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and planned to build a Garden Suburb-style village for the workers, but the financial pressure of the new factory was too great, and they reluctantly had to scrap the idea. The new factory produced both scientific glass and table glassware.

Thanks to the innovations of Harry, the new glass was more colourful, and the new wheel engraving in geometric designs epitomised the roaring twenties and the Art Deco style.

This period also saw the rise of James Humphries Hogan, who had started work with the firm at age 15 in 1898. He designed some very important cathedral windows, most notably those in the Lady Chapel of Liverpool Cathedral and St. Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue, NYC. As well as being a famous stained glass artist. Hogan also designed the stemmed glassware for use in British Embassies right around the World.

Hogan rose through the company, becoming Chief Designer (1913), Art Director (1928), Managing Director (1933), and finally Chairman in 1946. He was a workaholic and travelled regularly to America, where he increased Powell & Sons’ stained glass sales by 1000%. He returned home from a long US sales trip near Christmas 1947, collapsed on January 3rd, 1948, slipped into a coma, and died on January 12th.

WWII and Whitefriars Glass

Glass production pretty much halted at the outset of World War II and after the war, the firm struggled to regain profitability. Many skilled workers had been killed in the war; rationing continued into the fifties; and a fire at the factory all took its toll.

Glass production pretty much halted at the outset of World War II and after the war, the firm struggled to regain profitability. Many skilled workers had been killed in the war; rationing continued into the fifties; and a fire at the factory all took its toll.

The Festival of Britain in 1951 helped jumpstart the economy and the fortunes of Whitefriars who had been chosen to exhibit there. In 1954, Geoffrey Baxter joined the factory straight from the Royal School of Art, and he would later develop the psychedelic style of glass for the company in the swinging sixties.

The factory changed its name to Whitefriars Glass in 1963 and began using the monk logo. In the mid-sixties, Baxter began work on a new style of glass suitable for the era. This was to be a moulded design rather than the traditional Whitefriars hand blown glass.

Whitefriars Textured Glass Range

The textured glass prototypes were made using all kinds of materials. Bits of bark, nails, and wire were used to produce the textured range of glass. The range, with its distinctive Drunken Bricklayer and Banjo shapes, was launched in 1967 with three colours: willow, cinnamon, and indigo; vibrant tangerine, meadow green, and kingfisher blue followed two years later.

The Studio Range was also unveiled in the 1960s, but they were difficult and expensive to make and were discontinued after just a couple of years. They were the only ones ever signed by Whitefriars, with ‘Whitefriars’ and the date engraved on the base.

Success waned for Whitefriars in the seventies, with the exception of the Glacier Range of 1972 and the rise of the millefiori paperweight in the late seventies (which they had been producing since the 1930s). Unfortunately, by the end of the 1970s, with the fuel crisis and the recession, the factory was in financial trouble once again, and it sadly closed in 1980.

The factory was soon bulldozed to may way for housing developments and the ‘Whitefriars’ trademark was purchased by Scottish glass maker Caithness and is still used today for its paperweight range. The Whitefriars archive is at the Museum of London.

Whitefriars Glass: Real or Fake

With the increasing popularity of Whitefriars Glass and the rise in value of Whitefriars Glass and also the fashion for retro design, there are many Whitefriars fakes.

With the increasing popularity of Whitefriars Glass and the rise in value of Whitefriars Glass and also the fashion for retro design, there are many Whitefriars fakes.

This article by Mark Hill will help you tell the real ones from the fakes.

Dr. Rodina Prince has collated a detailed history of Whitefriars Glass; click HERE to see the website.

by Barnaby Kirsen – Boha Glass

Hello in the late 1960’s I bought a whitefriars amber coloured vase. It still has the whitefriar ticker on the vase. Does this vase have any value

Yes, put it on Ebay and you might get £20+ for it.

My grandad worked for whitefriars in the sixties . When he left he was presented with a whitfriars horse . I can’t find any other horse like this in thier range . I know my horse wA definitely made there please help thankyou sharon freeman

It sounds like a one of a kind, made after normal working hours. Like they did at Nailsea Glass.

So would my horse have a valuation . Can you please give an idea many thanks

HI, My dad Raymond Charles Smith did an apprenticeship at the factory in the mid-late 50’s or early 70’s. Does anyone recognise his name?

Your father may have known my uncle as he was working in Wealdstone at Whitefriars around the late sixties / seventies,. Kenneth Tyler.

Hi, my uncle worked for Whitefriars at the Wealdstone factory, his name was Kenneth Tyler, and I’m lucky to have a glass bowl he made

Hello my stepfather Peter Conway worked there before and after the war up until the end of the 60s. I’ve made an animated film about his early life in Harrow.

You can see the film here https://vimeo.com/474148670

Hope you like it.

Hi I’m in Australia, I have a Whitefriars s7 vase , on the bottom it has Whitefriars s7 1969, can anyone help me with a price or possibility of selling, it is the orange and aubergine range by Peter Wheeler

Grandfather John Edward Afford worked for Whitefriars and did the Mosaics in St. Paul’s Catherdral London. He got the Freedom of the City of London. Do you know what that was? Was it a certificate. And would you have any history of this for me please? He did the Fishes in one of the Domes.