Iridescent Dreams: The Story of Louis Comfort Tiffany

There is no question that in the realm of Art Nouveau glass, and within the aesthetic of Art Nouveau as a whole, Louis Comfort Tiffany is the stuff of legend. Best known for being the father of Tiffany art glass, Louis Tiffany helped to establish America as an epicentre of the formerly European movement, bringing to that rough and wild country the shimmering stuff of dreams, the fine curves and details of exquisite design.

Like Rene Lalique, Louis Tiffany was an artist who danced across mediums with ease; the span of his career would see him master the creation of stained glass windows and lamps, glass mosaics, blown glass, ceramics, and even dabble in jewellery and metalwork—he would cultivate not merely skills, but a complete and all-encompassing artistic vision. Likewise, in the same way that Lalique embraced the technological miracles and knowledge that arose from the industrial revolution, Tiffany would prove himself a keen innovator, experimenting with the possibilities of electric lighting right alongside Thomas Edison and working extensively with the chemistry of glass.

Tiffany: Influences and Beginnings

It is clear from what we know of Louis Comfort Tiffany that he was not driven to achieve all he did for worldly reasons. Born in 1848, Tiffany was the son of a prominent New York jeweler, and his father had already amassed a family fortune of $35 million U.S. dollars—a truly staggering sum in that era.

Rather than squandering this wealth, Tiffany invested in himself, studying art first in New York, and then later in Paris. Serendipitously, while in France, he encountered Emile Galle, the most famous artist of the Ecole de Nancy and a revered expert in glassmaking. While Tiffany’s attentions were not then resting on glass as exclusively as Galle’s were (Tiffany was mostly interested in Japanese prints, Middle Eastern art, and ancient Roman pottery, with a strong focus on painting in oils), Galle nonetheless proved to be a powerful influence on the style of Tiffany art glass in later years.

While Tiffany retained a focus on oils when he first returned to America, he gradually extended his artistic activity to encompass the whole field of decorative arts, likely spurred on by the holistic theory of Aestheticism and Art Nouveau (wherein life and art were not regarded as being separate entities, but rather irrevocably entwined). To this end, in 1875, he founded Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated Artists (renamed Tiffany Glass Co. in 1885, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Co. in 1892, and Tiffany Studios in 1900), enlisting the skills of over a hundred renowned craftsmen. Tiffany evidently chose them well, as within just a few short years, the interior designs of Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated Artists were in almost overwhelming demand—a fact which culminated in the firm restyling a suite of rooms in the White House in 1883, cementing Tiffany’s reputation as something remarkable.

It was this experience with interior design which proved to be integral in moving Tiffany’s attention over to art glass; as his company worked with tiles, lamps, murals, and windows, Tiffany became fascinated by glass, by the way it could be used to so artfully set off the colour and overall ambiance of rooms. He learned to combine glass with sumptuous textiles, jewels, and pottery (often incorporating Middle Eastern and oriental influences) to create breathtaking interiors for New York’s wealthy elite.

Tiffany Art Glass: The Ascension and the Renaissance

Tiffany’s glass first rose to the level of true art when he turned his hand to stained glass windows; emulating the windows of great cathedrals (which would soon come to request his services), Tiffany executed sublime paintings with glass as the medium—windows which drew the viewer’s eye into them rather than through them.

These windows were crafted in clear or opaque vari-coloured glass in complex designs intended to reflect light like the facets of a fine gemstone. To achieve this effect, Tiffany used many small pieces of glass, cut to shape and leaded, in patterned formation. (He also used opaque glass tiles, but usually to decorate walls, mantelpieces, and screens.) These techniques were unique at the time; according to Louis Comfort Tiffany: Artistry, Chemistry, Secrecy by Maureen Byko, “Unlike stained glass artists of his time, Tiffany mixed the colors into his glass rather than painting them onto it. Experimentation in his labs, conducted by skilled chemists and glass workers, found that the addition of gold to a batch of glass would give red; cobalt, blue; uranium, yellow; iron oxide, green. For every color needed, for every leaf or blade of grass, a new formula was found that provided the required shade.”

Tiffany likely began to segue this experience into smaller, more consumer-oriented art and glass pieces when, in 1885, he was commissioned to design sconces for the Lyceum Theatre in New York (it was then he worked closely with Thomas A. Edison, who installed much of the electric lighting). By 1906, Tiffany Studios had branched out widely into the world of lighting, selling over 400 models of electric and oil lamps and hanging shades.

These lamps were a resounding success for Tiffany, selling like wildfire both in America and abroad. Generally, they were comprised of tiny pieces of glass which were set in natural patterns (true to the motifs of Art Nouveau), usually featuring flowers, butterflies, or dragonflies. These designs were complemented by bronze bases and leaded or pressed glass shades (with the latter emulating the appearance of a tweedy fabric).

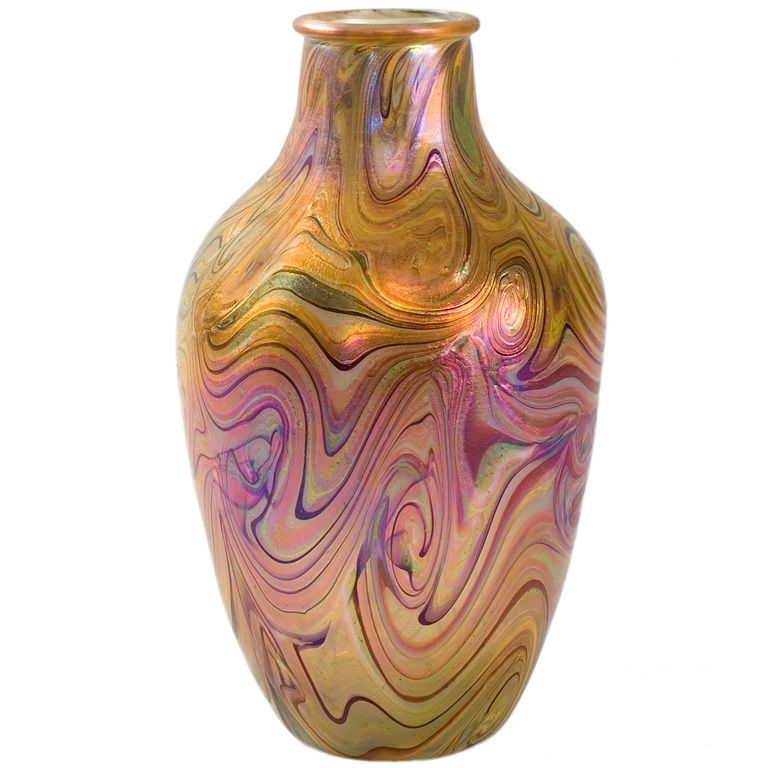

When he first began his more commercial glass endeavours, Tiffany used glass sourced from outside firms, but he soon grew dissatisfied with doing so. Becoming ever more enraptured by the possibilities of glass, he drew on his long-standing fascination with Roman art and experimented with lustering techniques in an attempt to replicate the delicate iridescence of ancient Roman glass. In these efforts he was amazingly successful, leading to the patenting of his first glass-lustering technique in 1881: Favrile glass, Tiffany’s most famous hand crafted glass, was born.

Favrile glass was made through the dissolving of metallic oxide salts into molten glass, creating a stunning array of colours: soft greens, blues, golds, etc. In order to create the hallmark lustre, the metallic content had to be brought to the surface through the application of a “reducing flame” and the spraying of chloride. This process caused the surface of the glass to develop subtle crackles all over it, refracting light.

Creating Favrile glass demanded much of glass blowers (all Tiffany glass was free blown); the blower had to work very quickly in order to achieve the desired effect, as if he allowed the molten glass cool, it would be too late. Given the intricacy of Tiffany patterns and designs—such as the peacock feather motif or the jack-in-the-Pulpit vase—one can only imagine the delicate dance the glass blower had to perform.

As his renown grew, Tiffany set up his own glasshouse (called Tiffany Furnaces) at Corona, Long Island, hiring the brilliant english chemist Arthur J. Nash to aid him in creating decorative blown glassware as chemically unique as it was aesthetically unique. Tiffany and Nash were notoriously secretive about their glass formulas, so much so that it is recorded that Nash “reportedly never shared [many of his formulas] even with Tiffany himself. Not that it mattered. Tiffany, experts in art and glass agree, was not a master of chemistry but of artistry and industry. He hired the best people he could find to execute his vision of painting nature in glass.” (Louis Comfort Tiffany: Artistry, Chemistry, Secrecy, Maureen Byko)

Tiffany never took a back seat to his skilled chemists and craftsmen, however; he remained fascinated with the capabilities of glass in the furnace, frequently coming up with diverse new ideas which he would not abandon even when Nash, after repeated attempts to see them through, grew convinced they were plainly impossible. This stubbornness wound up costing Tiffany a great deal of money—enough that despite the popularity of his glass, his company actually lost money over the years, and without the backing of Tiffany’s substantial fortune, it likely would not have survived as long as it did. But, while “such interference was not cost effective… it was symptomatic of what he was trying to do. He was a leader and Tiffany glass was never a shadow of other men’s work.” (The History of Tiffany Art Glass, StudioSoft)

Like all great originals, Tiffany spawned a host of imitators; these took the form both of hacks producing outright fakes and of some respectable glass houses emulating his techniques with due credit and appreciation. Foremost among the latter is of course Loetz of Bohemia. Loetz also used the furnace rather than the workbench to create its many impressive decorative effects, showing a true expertise that closely mirrored its American inspiration. Loetz, however, utilised a different business model; where Tiffany remained the stuff of luxury throughout its existence, Loetz produced a vast quantity of free-blown iridescent glass priced for the average consumer (making its consistent quality all the more appreciable).

Tiffany retired from his firm in 1918, leaving it in the capable hands of Nash, though it is said that he stayed on as an unofficial advisor, keeping a close watch on the company. While Tiffany glass remained a great pinnacle of the union between art and glass for about a decade, it did not make the transition into Art Deco gracefully, losing some of its trademark quality in the late 1920s. No doubt frustrated by this, in 1928 Tiffany severed all connection with the firm, and no longer allowed his name to be attached to its pieces. As was the case with all too many of the great glass houses of yore, Tiffany glass ended its once peerless dominance of the art glass world in a state of bankruptcy around the same time that Tiffany himself passed away in 1933.

From there, Favrile glass pieces and other Tiffany wares slumbered quietly in attics around the world until, in the 1970s, they began to take the world of antique art glass collecting by storm. Tiffany’s unique and remarkable blending of classical motifs with experimental—and in many cases inimitable—production techniques has left us with a legacy that today is more appreciated than ever, a testament to the capability and ingenuity of American artists and bold evidence for the stunning possibilities of glass as a medium for art.