During a prior retrospective on the life and art of Canadian glass sculptor James Houston published here at Boha, the subject of Steuben glass naturally arose; namely, that the firm, once reputed to produce the clearest crystal on Earth, had closed its doors—presumably forever—in 2011. However, what appeared to be yet another sad end to a once-distinguished producer of art glass, ushered in by a combination of economic turmoil and mismanagement, may as yet open to a bright new chapter: In 2015, Steuben will be revamping a portion of its historic design range and adding to it in in a highly selective manner in order to help support the illustrious Corning Museum of Glass.

The Rise of Steuben Glass

This year will certainly not be the first time Steuben Glass has reinvented itself; throughout its 108-year history, the firm moved from producing iridescent glass which rivaled that of its main competitor, Tiffany Glass, to creating matchless clear crystal vases, urns, and dinnerware, to pushing the boundaries of luxury art glass sculpture.

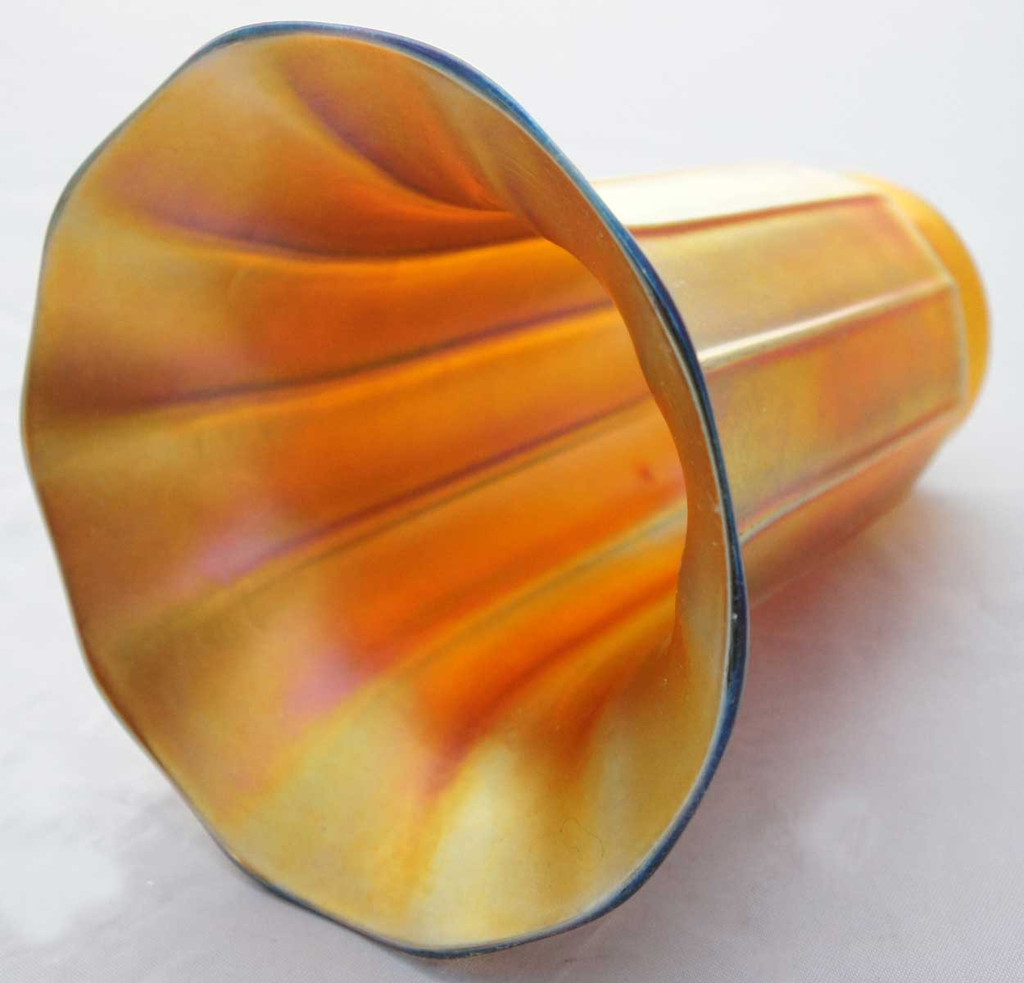

Steuben glassworks began in 1903 when Thomas Hawkes, a glass engraver, and Frederic Carder, an English glassmaker who specialised in colourful Art Nouveau glass, struck up a partnership. Carder was every bit as devoted to mastering the properties and possibilities of glass as the other glass heavyweights of his day, experimenting until he created a new form of iridescent glass which he named “Aurene”. While some saw Aurene glass as an attempt to replicate Tiffany’s wildly popular Favrile style, others viewed it as a distinct entity; where Favrile was rather dense and dark in nature, Aurene was light and lustrous, capitalising on the public’s desire for objects that would help to accentuate the sparse indoor lighting of their homes.

While Aurene was granted a patent in 1904, officially marking it as unique, Tiffany nevertheless filed a lawsuit against Steuben for “copying” its line. The case was, of course, ultimately shelved after Carder made the succinct observation that the Bohemians had been creating iridescent glass since the middle of the 19th century, long before Tiffany’s own 1894 patent. Carder also used dramatically different designs: Where Favrile’s forms and surface decorations followed the organic and naturalistic aesthetic of Art Nouveau, Steuben always leaned toward a cleaner and more classical look.

With that dispute resolved, Steuben’s Aurene glass was free to ascend to the heights of early 20th-century consumer demand. Among the most popular hues were gold (sometimes paired with white or shades of green or red) and blue. The latter often came in the form of elegant vases with concave bodies and ruffled rims, or later (during the 1910s) in the form of tall Egyptian-style vases with collared necks and high shoulders.

By 1918, the firm was feeling the effects of World War I; both the rationing of lead and the economic downturn that arose from the war threatened the survival of Steuben Glass, forcing Hawkes and Carder to sell it to nearby Corning Glassworks, whereafter it became a division of the larger company.

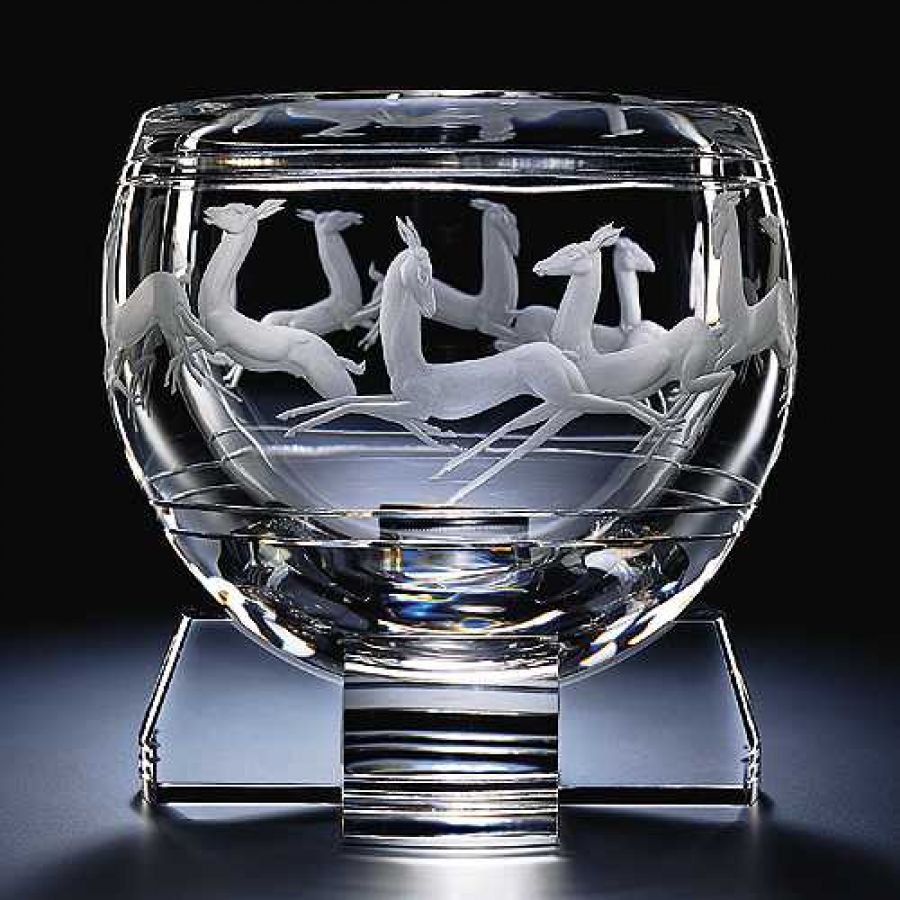

For a time, perhaps surprisingly, there was little change or upheaval at Steuben regardless of this manoeuvre; Carder plodded on, retaining his classical predilections with only minor revisions, such as the use of acid etching on his vases (in order to reflect the changing tastes brought about by the Art Deco movement). Notable pieces from this era include a stunning white vase replete with acid-etched dear leaping through the wilderness, Asian-style pieces which featured green-on-green patterns of curly-cues and fanciful dragons, and the acid-etched floral “Cluthra” vases, which introduced the additional use of air bubbles trapped just below the surface as a decorative element.

As expertly-made and visually delightful as these pieces were, the public’s desires were quickly moving beyond Carder’s somewhat antiquated preferences, and Steuben’s revenues began to fall sharply. (While the division had actually never been profitable, it is thought that the looming depression threw these new more severe losses into stark relief, prompting action from Corning.) Finally, in 1933, Carder was unceremoniously dismissed and replaced with sculptor Sidney Waugh in an effort to usher in a new era at the faltering glassworks.

There was just one problem: The warehouse remained packed to the rafters with the prolific Carder’s wares (the designer had produced more than 6,000 shapes in some 60 unique colours and designs during his tenure at Steuben, and evidently did not much slow his pace even as demand waned. In one of the more shocking events in art glass history, those pieces which could not be sold as mere “factory leftovers” were shattered into pieces on site in an event that went down in local history as “The Smashing”. The element of spectacle was intentional; “Steuben had a well-publicised event where they literally staged the public destruction of Carder Steuben glass,” explains Corning Museum of Glass creative director Rob Cassetti. “They destroyed it in front of the public.”

Waugh then proceeded to take Steuben in a brave new direction, moving away from coloured glass entirely and pioneering a new form of clear crystal. This change was as much due to evolving technology as Waugh’s personal taste; the chemists employed at Corning Glass had devised a recipe called simply “10M” which allowed the full spectrum of light to pass through it, including ultra-violet waves, resulting in a clarity of glass hitherto thought impossible. At this juncture, Steuben reinvented itself as a true luxury brand, a status symbol for the elite, soon becoming the stuff of state gifts (e.g. the set of engraved plates famously given by Harry Truman to Queen Elizabeth the Second). “One of the vision documents that was written at the time stated that the idea was that Steuben should be perceived as luxurious and almost as unattainable as a Cadillac,” says Cassetti.

Steuben also “got with the times”, fully transitioning into the world of Art Deco with a range of large cut or blown bowls and vases engraved using copper-wheel techniques. A 1935 piece called the Gazelle Bowl epitomises the very best of this period, followed by Waugh’s Zodiac Bowl and a vase called the “Agnus Dei”, all featured at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

During the 1940s Steuben extended its creative reach, collaborating with 27 internationally renowned artists, including Georgia O’Keefe, Henri Matisse, Isamu Noguchi, Salvador Dali, Paul Manship, and Thomas Hart Benton to create a public exhibition. The fervor over this event was such that Steuben frequently had to lock the doors of its Fifth Avenue store in order to control the flow of the crowd and prevent all-out havoc.

As World War II did not impact America nearly so severely as it did Europe, Steuben was able to weather the war years with relative ease, sailing into post-war prosperity with the works of designer Walter Teague, who turned the drawings of John J. Audubon into a very successful series of engraved 10-inch plates, and with the creation of its signature crystal hand coolers, designed in the rounded shapes of animals. The company also honed the “total package” that emphasised the cachet of its brand, becoming known for its beautiful packaging and presentation.

Steuben then began allowing their designers to create highly individualised art pieces, which ranged from abstract geometric shapes to Houston’s intricately detailed scenes of northern life.

Hard Times

While Steuben’s run as an icon of Western art glass lasted into the early 1990s, the death of famous contributors like James Houston and yet another major shift in public demand (the desire for crystal had long been in decline, a fact exacerbated sharply by the 2008 financial crisis) once again forced the aging firm into the position of having to innovate or face extinction.

Sadly, this time, the turnabout was neither dramatic nor revolutionary; in a move perhaps even more destructive than “The Smashing”, Corning sold the Glassworks to Schottenstein Stores Corp., a retail-chain operator based in Columbus, Ohio.

This led to a sad chapter of lacklustre new designs, cheap engraving methods which did a great disservice to Steuben’s proud legacy, and, for the first time in its history, production was offloaded overseas. The prices for many of Steuben’s wares thus fell to around 100 U.S. dollars each, ultimately destroying any vestige of luxury and status clinging to brand, moving it away from the forefront of Western art glass and into the mediocre realm of the department store. The long-held fear of many historians—that Steuben’s uncompromising dedication to materials, craftsmanship, and design might someday meet its end if the need to actually turn a profit arose—seemed to have come to pass.

“They totally lost their way,” lamented Jeff Purtell, a Steuben dealer in Portsmouth, N.H. “If your design department is pathetic, your costs are prohibitive, and your marketing — and vision for the future — is not successful, then you’re doomed whether you’re making Steuben glass or Twinkies.”

Schottenstein Stores Corp., the operator of U.S. retail chains Value City Furniture and DWS shoe stores, was trying to emulate Baccarat, Orrefors and Waterford Glass by tapping into a more diverse array of markets, but the strategy that saved so many European glassworks simply did not translate well in the U.S.

Corning, realising the error that had occurred, bought back the iconic Steuben brand, but no one truly held out hope that the “lodestar of lead crystal” would ever be produced again—a fact which deeply saddened many devoted collectors of Western art glass, who saw it as the end of a great era.

“I often wondered why the last generation, maybe two, cut down on Steuben,” mused collector Thomas Dimitroff. “The young folks don’t want it. Same thing with silver. There’s a different attitude. Every year we’re getting further away from the Victorian love of clutter, quality or not.”

Glassmakers, too, mourned the loss; Max Erlacher, a master engraver from Austria, was aghast at the change in Steuben:

“When I first came here in 1957, it was just a shining star,” he said. “Other companies like Baccarat of France did fabulous glass and still do, but they never had that quality of engraving. But even they’re going downhill because they don’t have the clientele.”

All totaled, enthusiasts felt they could look upon just one silver lining glimmering amidst the darkening clouds of a changing world: The aftermarket was likely to prove vibrant and enduring. As Purtell put it, “Tiffany art glass hasn’t been made since the 1930s, and the desirability did not diminish, it’s increased.”

The Rebirth of a Legend

Just when it seemed that the pages of history had turned forever, relegating Steuben to a past chapter wherein stunning craftsmanship and Objets d’Art had not yet been supplanted in the public imagination by the wonders of the digital era, the timeless American phoenix rose once again from the ashes:

“Steuben is pleased to announce that the tradition of Steuben Glass is continuing in 2015,” reads an announcement on the company’s website. The firm, it would seem, is returning to its roots as a prestige brand, promising that “Items are once again being produced by independent artisans in Corning, NY, and select European production shops. These exquisite products are being retailed exclusively through The Corning Museum of Glass. Additional items, both old and new, with Steuben’s ongoing commitment to quality design, craftsmanship and material will be introduced as part of the Iconic Reintroduction series.”

Once again, with a new era comes a new innovation in the technology of glassmaking: Steuben also claims that its pieces will henceforth be created in a new, lead-free crystal.

While it is, of course, early days for this new venture, the future appears to be as bright as the famous facets of Steuben’s crystal; Houston’s stunning “Trout and Fly”—priced at a hefty $4200—is already unavailable due to “overwhelming demand.”

Ahh — the Leaping Trout! In 1969, this beautiful Steuben piece was my greatestt desire. It was quite expensive, of course, but my husband was very generous, so I told him that this was all I wanted for Christmas. It would be the crowning treasure of my glass collection. Imagine my crushing disappointment when on Christmas Day my husband gave me — a mink coat, probably the last thing I wanted. Not only had it cost more than the trout, but he had sold some of our investments to buy it. He knew I was disappointed, and he explained that he had driven all the way to the Steuben store in New York to get it for me, but they refused to sell it to him because they were out of the special boxes that it was supposed to come in.

What could I say? To this day, that mink coat hangs in my closet, virtually unworn, while the Leaping Trout remains my unattained treasure.

Ah Marcia! Unrequited love! A leaping trout over a forlorn fur, any day!

The Gazelle bowl and Eskimo ice fisherman are, in my eyes, the greatest designs in glass ever conceived. I can’t afford to add either to my collection, but I’ve been lusting after them for years.

I was truly sad to read that Steuben lost its way for a time…and am relieved to know that their kilns have fired up once again!

I have some very Rare Steuben glass I would like to sell interested 5863711953 text or call. 1 of a kind or 1 of very few signed Steuben you probably never seen