From Venice To Fenton Art Glass: The History Of Milk Glass

In the world of art glass, much is said about the appeal of whirls of colour and shimmering iridescence; from the many-faceted delights of millefiori to the distracting gasoline glimmer of carnival glass, both collectors and glassmakers have drawn centuries of enjoyment from the clever manipulation of hues and tints. Sometimes, however, it is an absence or uniformity of colour which truly lets us appreciate the grace of form and the intricacy of detail that is the hallmark of any great piece of glass—a concept embraced and embodied by the highly collectable form of art glass known as “Milk Glass.”

In the world of art glass, much is said about the appeal of whirls of colour and shimmering iridescence; from the many-faceted delights of millefiori to the distracting gasoline glimmer of carnival glass, both collectors and glassmakers have drawn centuries of enjoyment from the clever manipulation of hues and tints. Sometimes, however, it is an absence or uniformity of colour which truly lets us appreciate the grace of form and the intricacy of detail that is the hallmark of any great piece of glass—a concept embraced and embodied by the highly collectable form of art glass known as “Milk Glass.”

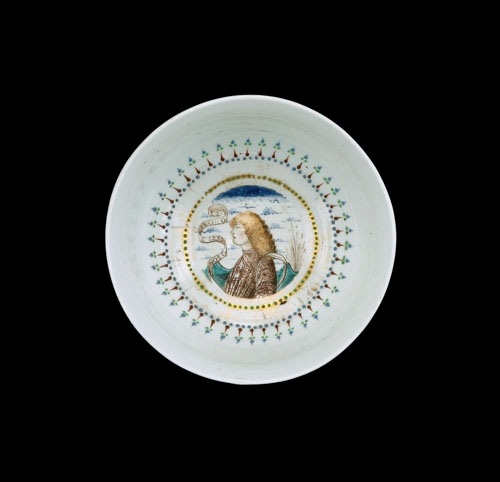

Though Milk Glass is most frequently associated with 19th century America and the fresh opulence of that nation’s Gilded Age, as is the case with so many art glass manufacturing techniques and traditions, Milk Glass has its origins in the Venetian islands of Murano. During the heyday of Murano’s glassworks—the period of great technological innovation which took place on the islands from the mid-15th to the mid-16th century—the renowned glass artist Angelo Barovier combined generations of  Barovier family knowledge with his own flair for scientific exploration, refining many of the primary materials used in glassmaking and experimenting with them in creative new ways. In addition to discovering the first truly clear crystal glass the world had ever seen, Barovier also mastered a technique he called “Lattimo”, a white glass believed to be an imitation of the pure, cool opaqueness achieved by Chinese porcelain.

Barovier family knowledge with his own flair for scientific exploration, refining many of the primary materials used in glassmaking and experimenting with them in creative new ways. In addition to discovering the first truly clear crystal glass the world had ever seen, Barovier also mastered a technique he called “Lattimo”, a white glass believed to be an imitation of the pure, cool opaqueness achieved by Chinese porcelain.

Though the glassmakers of Murano struggled in later centuries to keep up with the innovations of Bohemian artists and the incredibly precise crystal-cutting of the English, Lattimo (like another Venetian export, Avventurina) remained popular well into the 18th century, enduring right up until the collapse of the Venetian economy in 1797.

The American Rebirth Of Milk Glass: Manufacturers, Composition, And Cultural Role

Due to the English blockade that was imposed during the Napoleonic wars and an oppressive half-century of Austrian rule (which saw tariffs placed on imports of the raw materials needed to produce glass) Lattimo, like so many great Venetian techniques, would spend years brushing shoulders with obscurity.

Fortunately, as the size of the American upper and middle classes increased and the demand for attractive consumer goods grew in the New World, a number of American glass manufacturers stepped in to rescue the concept of Lattimo from an untimely end. During the latter half of the 19th century, American glass manufacturers like Westmoreland, Imperial, Indiana, Anchor Hocking, and the Fenton Art Glass company would begin to produce their own take on Lattimo—Milk Glass—as an economical substitute for the expensive glass, crystal, and porcelain then being made in Europe and China. (Milk Glass became fashionable in America largely thanks to the initial efforts of French glassmakers like Portieux, who revived the desire for opaque glass amongst the French elite; this inspired newly wealthy American families to follow suit.)

While Fenton was a relatively late addition to the world of Milk Glass manufacturing (the revival having begun in Europe in the 1870s and Fenton having been founded in 1905), today Fenton art glass is perhaps the most strongly associated with the trend owing to the enduring quality of its wares; unlike the other “great name” of American Milk Glass, Westmoreland, the quality of Fenton art glass did not decline markedly after the postwar period—indeed, the timeless appeal of Fenton’s Milk Glass is often regarded as one of the main reasons the company has weathered its own difficult times (the company’s wildly popular mid-century Hobnail Milk Glass line was referred to as “our bread and butter” by Bill Fenton).

Though Victorian Milk Glass reflected its Venetian predecessor in appearance, it differed in composition. Medieval Lattimo was created by using a compound of lead and tin as opaquing agents—an idea which was, of course, revolutionary for its time, but which produced a more crude and less versatile glass than that which could be created using the more technologically-advanced techniques of the Gilded Age.

From the 19th century onwards, Milk Glass was manufactured with a range of different opacifiers; at first, glassworkers used arsenic in their glass mixtures (which resulted in a dull yet opalescent hue), while later versions of Milk Glass were formed from compounds of bone ash, antimony, and tin dioxide. These composite formulas often resulted in a deeper, more purely white hue. There is, however, a lot of variety in the Milk glass produced during this era; Milk glass manufacturers experimented freely with controlling the size distribution and density of the particles in their opacifiers of choice, creating glass that ranged from lightly opalescent in nature to opaque white. Other colours, notably pale blue, green, and black, were also added to the milk glass range.

From the 19th century onwards, Milk Glass was manufactured with a range of different opacifiers; at first, glassworkers used arsenic in their glass mixtures (which resulted in a dull yet opalescent hue), while later versions of Milk Glass were formed from compounds of bone ash, antimony, and tin dioxide. These composite formulas often resulted in a deeper, more purely white hue. There is, however, a lot of variety in the Milk glass produced during this era; Milk glass manufacturers experimented freely with controlling the size distribution and density of the particles in their opacifiers of choice, creating glass that ranged from lightly opalescent in nature to opaque white. Other colours, notably pale blue, green, and black, were also added to the milk glass range.

What makes American Milk Glass truly remarkable, however, is not the quality of its composition (indeed, many collectors view French Milk Glass as the finest overall), but rather the versatility of its forms. Everything from tableware and dinnerware to clocks, inkwells, jars, lamps, vases, candlesticks, matchstick holders, and even costume jewellery were rendered in smooth, gleaming Milk glass. Many of these pieces showed a breathtaking attention to detail, featuring scalloped and delicately beaded edges, waffle and diamond patterns, and even whole reliefs depicting scenes of cultural and historic significance.

Some of the most valuable pieces of American Milk glass are plates crafted with a border of 13 stars and George Washington’s likeness, and the iconic plates that helped launch the 1908 presidential campaigns of William Howard Taft and William Jennings Bryan. There’s even an extremely rare platter adorned with an ornate relief of President Abraham Lincoln (probably used as part of dinner service at a commemorative event), covered dishes from the Spanish-American War that bear the likeness of Admiral Dewey, and plates (also circa 1908) celebrating Roosevelt’s first “Teddy” bears. As Bill and Betty Newbound (authors of The Collector’s EEncyclopaediaof Milk Glass) put it, “The whole history of our country can be followed in its glass.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the cultural significance of Milk glass, it is still in great demand today. Thanks in large part to the efforts of Fenton, who produced their hobnail line into the 1980s, American Milk glass is relatively easy to obtain on the secondary market, making it an excellent starting point for any budding glass collector. The National Milk Glass Collectors Society provides a wealth of information for anyone wishing to further explore this time-honoured glassmaking tradition.