Walking past the E.1027—a small white holiday house perched on a bluff overlooking the bay of Monaco—you wouldn’t notice anything out of the ordinary. Like most contemporary homes in the region, it’s characterised by sleek, clean geometric lines, a design that affords spectacular views of the surrounding area, and a light, airy mien. There is, however, one significant difference between this home and its peers: It was designed in 1926 and completed in 1929.

Walking past the E.1027—a small white holiday house perched on a bluff overlooking the bay of Monaco—you wouldn’t notice anything out of the ordinary. Like most contemporary homes in the region, it’s characterised by sleek, clean geometric lines, a design that affords spectacular views of the surrounding area, and a light, airy mien. There is, however, one significant difference between this home and its peers: It was designed in 1926 and completed in 1929.

The mastermind behind this innovative piece of architecture was not Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, or any of their well-known contemporaries. Instead, the E.1027 was designed by a middle-aged Irish woman whose name few remembered until recent years, when interest in her work was revived in the popular imagination. Perhaps this is unsurprising considering not only the architect’s gender, but also the fact that she was not trying to make history when she built the E.1027. Always one to shun self-promotion, Eileen Gray designer wise, was simply trying to design a holiday home for herself and her lover (Jean Badovici, editor of L’Architecture Vivante)—a relaxing retreat that suited her particular sensibilities. Indeed, she even initially allowed Badovici, who by all accounts struggled with a lack of real talent, to take the lion’s share of the credit for her design.

By the time Eileen Gray began seeing Badovici in the early 1920s, she was a self-made woman with her own means (funds she would often use to support Badovici’s ventures). She was an established interior designer with a popular Parisian gallery, Jean Désert, whose clients included the Rothschilds and Elsa Schiaparelli. Her lack of formal training in architecture did nothing to dissuade her from diving headlong into the design of a thoroughly modernist abode. After all, she was used to deftly turning her hand to new disciplines. Calmly and methodically, she taught herself drafting by studying the plans of Adolf Loos, Gerrit Rietveld, and Le Corbusier. She would not only astound the latter with the grace and ease she demonstrated in building the E.1027, she would correct him: She saw that the house is more than just “a machine for living,” as Le Corbusier purported. Under her careful guidance, it became much more; “A house is not a machine to live in,” Gray wrote. “It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation. Not only its visual harmony but its organization as a whole, the whole work combined together, make it human in the most profound sense.” To Gray, architecture was alive and breathing, not merely cold and supremely efficient.

Gray’s unique capacity for independent vision had been the guiding force throughout her life. Born Kathleen Eileen Moray in 1893 in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Eileen Gray could have wiled away her earthly existence without ever working. Her parents were the wealthy owners of a substantial estate and her mother had inherited the title of Baroness, which she attempted to pass on to her children. However, Eileen knew early on that resting on the laurels of her birthright was simply not for her. As author Brian Dillon wrote in The London Review of Books, Gray thought titles were pointless relics of antiquity; “trappings fit only for operettas.” Eschewing a life of ease, Gray enrolled in the Slade Academy of Art in London in 1898 to study painting.

Gray’s unique capacity for independent vision had been the guiding force throughout her life. Born Kathleen Eileen Moray in 1893 in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Eileen Gray could have wiled away her earthly existence without ever working. Her parents were the wealthy owners of a substantial estate and her mother had inherited the title of Baroness, which she attempted to pass on to her children. However, Eileen knew early on that resting on the laurels of her birthright was simply not for her. As author Brian Dillon wrote in The London Review of Books, Gray thought titles were pointless relics of antiquity; “trappings fit only for operettas.” Eschewing a life of ease, Gray enrolled in the Slade Academy of Art in London in 1898 to study painting.

Though Gray was a shy woman—and therefore often interpreted as being remote—she made a number of influential connections during her tenure at the Slade. She befriended the writer, painter, and critic Wyndham Lewis (who would later go on to co-found the Vorticist movement), along with potter Bernard Leach, explorer Henry Savage Landor, and sculptor Kathleen Bruce. She even allowed the infamous Aleister Crowley to court her, mostly because he was, in her words, “very lonely.” It was not until she passed by a lacquer workshop while on a walk in 1905 that a match was set to the tinder of fertile imagination, however. Enamoured with what she saw, Gray humbly approached the owner of the shop and asked him to take her on as an apprentice. After many hours of work—and a fruitful partnership with Japanese lacquer artist Seizo Sugawara—Eileen Gray Designer firmly established herself as one of the finest young lacquer artists in Paris, where she had by then taken up residence.

Naturally, Gray soon outgrew the limits of lacquer and expanded into the realm of interior design. In Paris in the 1910s, she mingled with a gender-bending, artistic milieu of eccentrics while extending her creative reach to touch furniture and rugs. However, while Gray’s interiors enjoyed great success almost immediately, her aesthetic still paid a great deal of homage to Fin-de-Siècle movements like Art Nouveau; her interiors were defined by curving lines and naturalistic motifs. It was only when she designed the Lota Apartment in 1922 that her modernist inclinations started to make themselves more evident. Within this interior was a piece of furniture rendered in a style that was unlike anything of its day: The black leather Bibendum Chair, which featured several sleek tubes curving around its base, one stacked on top of the other.

Naturally, Gray soon outgrew the limits of lacquer and expanded into the realm of interior design. In Paris in the 1910s, she mingled with a gender-bending, artistic milieu of eccentrics while extending her creative reach to touch furniture and rugs. However, while Gray’s interiors enjoyed great success almost immediately, her aesthetic still paid a great deal of homage to Fin-de-Siècle movements like Art Nouveau; her interiors were defined by curving lines and naturalistic motifs. It was only when she designed the Lota Apartment in 1922 that her modernist inclinations started to make themselves more evident. Within this interior was a piece of furniture rendered in a style that was unlike anything of its day: The black leather Bibendum Chair, which featured several sleek tubes curving around its base, one stacked on top of the other.

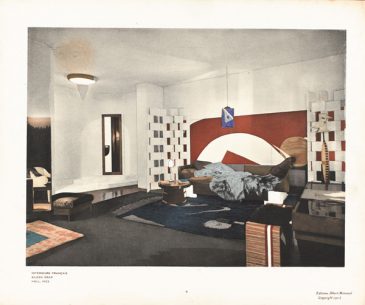

By the time Gray was invited to design a room to exhibit at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs, her new direction—and her unique vision—had firmly taken hold. Her completed work, the Monte Carlo room, contained white multi-hinged screens and austere furniture in a decidedly Cubist style. Like all truly original works of art, it violently divided critics upon its debut. Some decried it as a “room of horror,” while others celebrated its innate, stripped-down harmony. Badovici, evidently, was a fan; it was the Monte Carlo room that impelled him to seek Gray out and encourage her to try her hand at architecture.

In architecture, Eileen Gray Designer found the most complete release for her meticulous attention to detail. The E.1027 is a marvel of hidden storage and built-in features meant to enhance residents’ ease of living, such as a swivel table that allows the owner to eat in bed without fear of crumbs. As Brian Dillon described it, the E.1027 “Is a feat of compression as well as design: its two floors contain a living room, two small bedrooms, terraces, loggias, bathrooms and tiny quarters for a maid. Almost all the rooms give out onto the terraces, and a spiral staircase rises through the centre of the house to a glass cabin on the flat roof… Strip windows run the length of each floor, with an intricate system of five different types of shutter, some of them opening and sliding on rails, eliding the distinction between inside and outside. A staircase descends from the upper terrace to a sunken concrete solarium with built-in recliner, Gray having toyed with and rejected the idea of a pool.” At the same time, Gray never let her passion for efficient spaces overshadow real human needs. She avoided Le Corbusier’s theory of promenade architecturale (the idea that the observer should have a clear pathway through any built space), focusing instead on the creation of truly private spaces and the idea of home as one’s individual sanctuary. She believed that even in the smallest house, “Each person must feel alone, completely alone. The civilised man needs coherent form. He knows the modesty of certain acts; he needs to isolate himself.”

Unfortunately, Le Corbusier did not take well to Eileen Gray’s professional critique—despite the fact that she was also a great admirer of his. Le Corbusier “Coveted [the E.1027] with a professional regard that verged on personal spite,” in all likelihood envious of the way the frankly inexperienced Gray had upstaged more seasoned architects like himself. Thus began a long, troubled epoch in the history of both the house and Gray’s life. When Gray moved out of the E.1027 after her relationship with Badovici soured (Gray would never marry or have children, preferring to live unencumbered by domesticity), Le Corbusier moved in and painted a series of bright, garish murals on the walls of the minimalist abode—an act Gray openly called “vandalism.” Le Corbusier would even go so far as to build a wooden cabin nearby, so that he could gaze upon Gray’s creation. It’s even been reported that he died—from drowning—while swimming in sight of the home.

Unfortunately, Le Corbusier did not take well to Eileen Gray’s professional critique—despite the fact that she was also a great admirer of his. Le Corbusier “Coveted [the E.1027] with a professional regard that verged on personal spite,” in all likelihood envious of the way the frankly inexperienced Gray had upstaged more seasoned architects like himself. Thus began a long, troubled epoch in the history of both the house and Gray’s life. When Gray moved out of the E.1027 after her relationship with Badovici soured (Gray would never marry or have children, preferring to live unencumbered by domesticity), Le Corbusier moved in and painted a series of bright, garish murals on the walls of the minimalist abode—an act Gray openly called “vandalism.” Le Corbusier would even go so far as to build a wooden cabin nearby, so that he could gaze upon Gray’s creation. It’s even been reported that he died—from drowning—while swimming in sight of the home.

Eileen Gray Designer laboured on in relative obscurity, working sporadically as an architect and interior designer in France and taking up a very reclusive lifestyle. Meanwhile, the E.1027 changed hands several times, from Badovici to Le Corbusier’s friend Marie-Louise Schelbert, to her doctor, who was murdered on the premises by his own gardener in 1996. The iconic furniture within the home was auctioned off piece by piece, and the natural elements that Gray had carefully studied when designing the building (in order to allow for maximum light penetration and airflow) were allowed to take a heavy toll on its exterior. Had it not been for an alliance between Michael Likierman, a British businessman, Robert Rebutato, the son of the owner of L’Etoile de Mer, and the French government agency Conservatoire du Littoral, the house would have completely succumbed to damage.

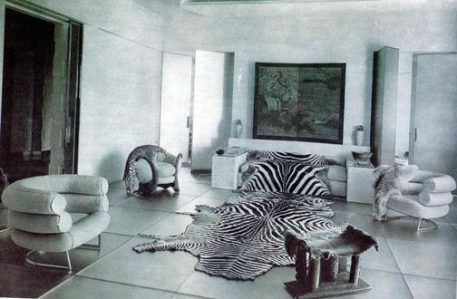

Today, the restored remains of Gray’s vision appear to be safe, at least for the time being. They speak of an independent woman’s often embattled quest to earn recognition on her own terms and bear many scars. Le Corbusier’s murals cannot be removed, given his own enduring status and their resultant importance; their colours still stand out in garish contrast to their surroundings, confronting Gray’s subdued genius. The bullet holes that were in them—the work of Nazi soldiers—have been patched over. Altogether, the E.1027 is a “rougher, cruder” place now than when it was first built, the privacy that was at the heart of Gray’s life and ethos having been thoroughly invaded. But, on the back wall of the main living space, one can still find the large nautical chart that Gray herself placed there, claiming that it “evokes distant voyages and gives rise to reverie.” Fortunately, something of Eileen Gray Designer dreams have been allowed to remain.