The prolific, troubled Norwegian artist Edvard Munch created some of the most iconic artworks of all time, including The Scream and Madonna. Edvard Munch art dealt with a series of dark and controversial themes, including sexual liberation and chronic illness.

The prolific, troubled Norwegian artist Edvard Munch created some of the most iconic artworks of all time, including The Scream and Madonna. Edvard Munch art dealt with a series of dark and controversial themes, including sexual liberation and chronic illness.

Munch, who was born in 1863, saw numerous family members experiences serious illnesses during his childhood, with his mother and sister both passing away at a young age. Munch’s Christian fundamentalist father interpreted their deaths as acts of divine punishment, which had a sizeable impact on the artist, whose works were largely centred upon suffering, pain, anxiety and vulnerability. Munch was a pioneer in the fields of Symbolism and Expressionism.

Edvard Munch art is synonymous with intense colour, with many of his pieces being focused on the sexual. The artist saw sex as a valuable channel for liberation from conformity, and as a way of exploring the nature of human psychology further.

Edvard Munch art is synonymous with intense colour, with many of his pieces being focused on the sexual. The artist saw sex as a valuable channel for liberation from conformity, and as a way of exploring the nature of human psychology further.

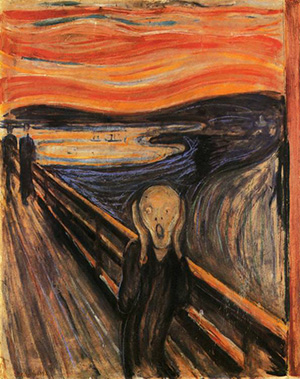

The Scream was created in 1893 and is seen as being part of a group of ground-breaking works from its era, which also includes Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It was created after Munch paid a visit to a mental hospital where his sister had been staying and he saw the sky turn “as blood as red” and heard “enormous, infinite scream of nature.”

Although it’s thought Munch created a large number of nudes in his early life whilst carving out his artistic niche, only one of these has survived, Standing Nude. Some historians have suggested that his devoutly religious father may have destroyed these works. Only sketches made prior to the completion of these works have survived.

Although it’s thought Munch created a large number of nudes in his early life whilst carving out his artistic niche, only one of these has survived, Standing Nude. Some historians have suggested that his devoutly religious father may have destroyed these works. Only sketches made prior to the completion of these works have survived.

Munch’s weak immune system meant he spent much of his childhood away from school learning how to draw and paint. The artist discovered the work of the Norwegian Art Association in his early teens and taught himself oil painting whilst attempting to recreate their works.

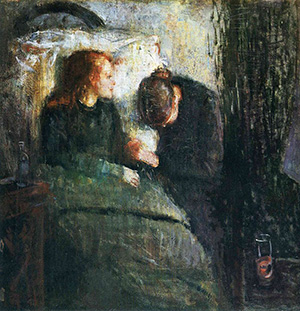

Munch spent much time reading the works of anarchist philosopher Hans Jæger in the 1880s. Jæger headed the Kristiania-Boheme group, who endorsed free love and called for marriage to be abolished. Munch and Jæger formed a strong friendship that led to the artist being encouraged to use more of his personal experienced as inspiration for his work. The Sick Child was created between 1885 and 1886 and was a memorial to the artist’s late sister Sophie. Whilst this example of Edvard Munch art is now seen as hugely influential, critics at the time panned the piece for its unfinished appearance, scratched paint surface and other subversive qualities.

Munch spent much time reading the works of anarchist philosopher Hans Jæger in the 1880s. Jæger headed the Kristiania-Boheme group, who endorsed free love and called for marriage to be abolished. Munch and Jæger formed a strong friendship that led to the artist being encouraged to use more of his personal experienced as inspiration for his work. The Sick Child was created between 1885 and 1886 and was a memorial to the artist’s late sister Sophie. Whilst this example of Edvard Munch art is now seen as hugely influential, critics at the time panned the piece for its unfinished appearance, scratched paint surface and other subversive qualities.

The artist created many of his works with the hope that viewers would reach their own interpretations of the pieces. Spring, which came after The Sick Child, was more mainstream in style and helped the artist gain state support to study in France. When Munch’s father passed away, he started to reject the writings of Hans Jæger, with the piece Night in St. Cloud reflecting his new interest in the spiritual. Munch was invited to exhibit his work in Berlin by the Berlin Artists’ Association in 1892, though his paintings caused much controversy. However, the publicity generated by the scandal helped Munch create more exposure for his work, and its popularity started to grow. He decided to remain in Germany, creating a new range of paintings called the Frieze of Life, which were fuelled by themes of death, love and anxiety. Munch started to make prints of his work to cater for a growing audience.

Munch entered a Danish hospital in 1908 after a nervous breakdown. The lithograph series Alpha and Omega included depictions of his love affairs and relationships between enemies and friends. Following the treatment, he returned to Norway, living a life of solitude and creating works that were more optimistic in nature, such as the Oslo University Aula murals.

Munch entered a Danish hospital in 1908 after a nervous breakdown. The lithograph series Alpha and Omega included depictions of his love affairs and relationships between enemies and friends. Following the treatment, he returned to Norway, living a life of solitude and creating works that were more optimistic in nature, such as the Oslo University Aula murals.

World War I saw the artists return to darker themes, focusing on love and death and creating various symbolic prints and paintings as well nudes and landscapes. The vast majority of Edvard Munch art produced between his time in the institution and his death were landscapes, which were often joyous in nature due to the loose brush strokes and vibrant colours that featured in them. Munch spent the later years of his life faced with partial blindness, editing diaries from his youth and creating bleak self-portraits and works based on his early life. Much died in Oslo in 1944, aged 80.