No series on the Ysart family would be complete without a chapter on their contribution to the history of Scottish paperweights. While the Vasart team and Paul Ysart (who by this era was estranged from his father and brothers, having remained at Moncrieff Glassworks) had vastly different outlooks on paperweights, each branch of the Ysart family contributed something meaningful to the genesis of Scottish paperweights as a whole.

Vasart Glass Paperweights

Vasart glass helped to popularise the concept of paperweights as decorative glass gift objects and souvenirs; in essence, as commodities. Their approach to paperweights was entirely different to that of Paul Ysart—rather than seeing paperweights as small art objects, they saw them strictly as novelty items. For Vasart, paperweights were a side line that was relied upon to bolster the small company’s often lacklustre income via the ever-booming gift trade.

As such, many Vasart paperweights are a bit rough around the edges, and certainly highly variable in nature; in order to keep production moving as the Ysart brothers and Salvador focused on other projects, work on the various decorative glass weights was frequently delegated. The wives of the Ysarts (and of a few other Vasart employees) were frequently given free hand to assemble the canes in the weights on their own. It has been recorded that “The canes were laid out by the women working in a caravan parked next to the Shore Road Works and not, as rumoured, by outworkers. When an additional shed was built for decorating, this was also used for paperweight assembly.” (Ysart Glass, Volo Edition, 1990) It is very likely that the struggling Vasart firm simply could not afford to take on more workers, and as such, drafted their wives into aiding them, despite their relative lack of experience.

This is not to say that all Vasart paperweights were the work of amateur hands (and therefore not worth the attention, as a whole, of more serious collectors); there are a smaller number of high-quality Vasart paperweights in existence, most likely made by The Ysart brothers and another skilled glassworker by the name of Jack Allen.

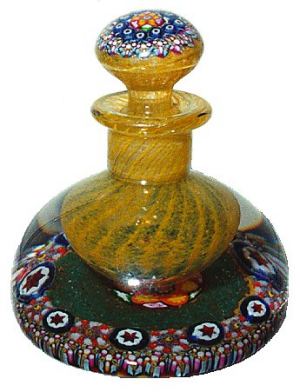

Vasart also produced a range of smaller decorative glass weights which are worth sifting through; these were generally used to decorate corkscrews, letter openers, and car gear stick knobs. Larger weights were also made; these were glued to brass door handles or crafted into door stops. Vasart even made a range of ink bottles with coloured centres; these had no likeness among Paul Ysart’s various pieces, as he always opted for clear centres. These ink bottles are known for being of especially consistent quality, and were very popular at the time of their manufacture.

(Vasart’s occasional bursts of quality seem to have been duly noted even by experts of that era; there is an anecdote floating around which suggests some of the better Vasart weights fooled an English professor who was travelling through Scotland buying millefiori objects for a museum. He bought several Vasart weights at an antique show believing them to be valuable heirlooms, before going on to discover they were modern and seek out the glassmakers responsible for crafting them).

Identifying genuine Vasart paperweights can be a bit of a challenge as Strathearn (the company which “absorbed” Vasart and carried on using their designs long after any actual Ysarts were present at the firm) continued the production of glass paperweights for many years. It’s useful to compare the paperweight you have against Strathearn weights, and look for the presence of dark tinted glass (similar to that which was used in Monart paperweights, but made with a much clearer metal) and a snapped-off pontil mark which has not been ground down significantly.

Likewise, as the Vasart company moved when it melded into Strathearn glass, its supply of materials changed and the chemistry of its glass was therefore altered. As such, Strathearn weights “are easily detected by the different range of colours and a strange ‘dry’ appearance when compared to the canes in their earlier work.” (Ysart Glass, Volo Edition, 1990) This change likely occurred because the colours caused issues when encased in the new form of clear glass, which is believed to have had a higher lead content than the glass the Vasart company had been using prior.

Other strong indicators that one has a weight from an early period include the presence of a “Vasart” signature: a black and white circular label, or an acid etched “Ysart Bros.” signature. Signed pieces are, however, rare as a general rule. Devoted collectors may wish to instead conduct research using UV light to accurately date their pieces.

There is one final consideration to take into account when searching for rare and high-quality Vasart paperweights: It is said that after leaving Strathearn, Vincent Ysart kept on making art glass paperweights as a hobby (using Vasart canes and a cold casting resin which had not been used at any time previously), right up until his death. To date, it is believed that none of these have turned up for sale, so to find one would be to unearth a rare gem indeed.

Here is an Inkwell from one of our readers Reg Reid: