Writing habitually about art glass and the history thereof is an experience that frequently mingles awe with a touch of sadness. The delicate beauty, intricate details, and sheer creativity that can be seen in so many great works of glass is enough to both take one’s breath away and to instil a renewed appreciation for the human spirit.

Writing habitually about art glass and the history thereof is an experience that frequently mingles awe with a touch of sadness. The delicate beauty, intricate details, and sheer creativity that can be seen in so many great works of glass is enough to both take one’s breath away and to instil a renewed appreciation for the human spirit.

The cruel hand of time is invariably felt, however, when one reads of how much has been lost, when one thinks of all the great artists who have left us and whose value may not have been fully realised until long after their passing, and when one observes how many once proud and noble companies have dwindled to bankruptcy during various economic recessions. The overall effect can be a sense of great loss; not simply the loss of these artists and many of their pieces, but of humanity’s appreciation for art and fine craftsmanship as a facet of daily life. Sometimes I have found myself wondering if we are experiencing an overall loss of beauty as we increasingly commodify all that we use, as we rush past everything around us.

Fortunately, the story of Caithness Glass goes a long way to counter such dreary perceptions. The tale of Caithness Glass is one of finding hope in unusual, inhospitable places, of carving handmade beauty from the wilds.

Fortunately, the story of Caithness Glass goes a long way to counter such dreary perceptions. The tale of Caithness Glass is one of finding hope in unusual, inhospitable places, of carving handmade beauty from the wilds.

Caithness is an area as vivid as it is harsh; it is the most northerly and remote county in Scotland, and Wick, where Caithness Glass was born, straddles the rocky and unforgiving coast of the northern Atlantic. Rain, sleet, and snow frequently dance across the region’s crystal-clear silvery waters and jewel green hills.

Naturally, eking out a living in such remote climes is no easy task, and resourcefulness born of this hardship is what led to the creation of Caithness Glass. One of the few reliable sources of revenue in the area is provided by the steady stream of tourists who come each year to marvel at the untamed landscape, and in 1961, enterprising local businessmen created a small glassworks that specialized in crafting vases and bowls to supply tourists with souvenirs of their time in Caithness.

This fairly common and humble trade unexpectedly linked with the world of art glass when, in 1963, the company hired Paul Ysart to train some of the local people to make glass. Paul, already renowned by that point for his paperweights, was the son of a Spaniard by the name of Salvador Ysart, who had immigrated to Scotland in 1914, and who came from a proud family of traditional glassworkers. Salvador had also studied at several glass houses in France, one of the great epicentres of art glass at the turn of the 19th century. All of Salvador’s sons continued the tradition, using their father’s knowledge to become masters in their own right. Paul, Salvador’s eldest son, “is generally recognized as the finest paperweight maker of his time.” (Robert Hall; Scottish Paperweights).

Naturally, Paul’s arrival began to transform the nature and scope of Caithness Glass. As the company did not make paperweights at that time, Paul taught his apprentices (Peter Holmes and Willie Manson) how to make them after work and on weekends, sharing with them his well-guarded techniques.

Naturally, Paul’s arrival began to transform the nature and scope of Caithness Glass. As the company did not make paperweights at that time, Paul taught his apprentices (Peter Holmes and Willie Manson) how to make them after work and on weekends, sharing with them his well-guarded techniques.

The seed of greatness had officially been planted. When, in 1968, Colin Terris joined the company (having been charged with setting up an engraving and design studio), he and Paul soon combined their knowledge, and Colin was subsequently struck by inspiration. Just one year later, in 1969, he designed the iconic “Planets”: A set of four abstract paperweights which coincided with mankind’s first landing on the moon, capturing something of the spirit of the public’s fascination with outer space, which was then at its zenith. The initial limited edition of 500 sets sold out rapidly, and the following year Colin designed and successfully marketed several more beautiful abstract paperweight designs.

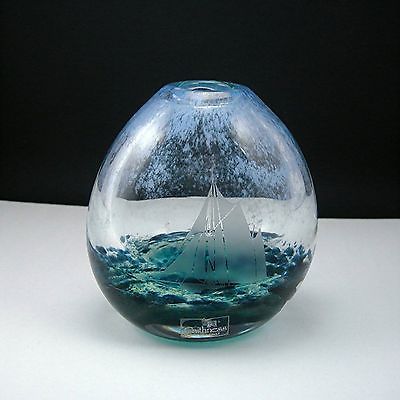

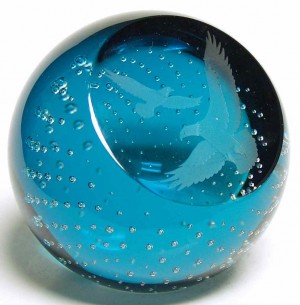

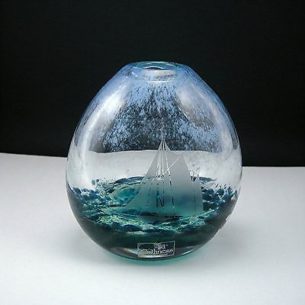

After this point, Caithness quickly grew into a major operation, producing paperweights, jewelry, clocks, vases, bowls, perfume bottles, and more, all in high-quality crystal and coloured glass, and in designs that frequently call to mind the landscape of Caithness itself—soaring eagles, waves whipping in the wind, etched yachts floating in the sea—giving the impression of holding a bit of Caithness’s wild spirit in one’s hands.

Caithness Glass eventually outgrew the tiny glassworks in Wick; today it is produced in several different cities, and the company employs nearly a dozen designers, including renowned glass artist Sarah Peterson. The firm has not outgrown its particularly Scottish flair, however—a quick browse through the current roster of designs reveals celtic knot work, proud purple thistles, and scenes of the sea, including a lighthouse bravely illuminating the forbidding Scottish shore that Caithness Glass calls home.