When most people hear the word ‘Bohemian,’ they envision eclectic decor, artfully loose, careless hair and clothing, and flamboyant jewellery, rich in the use of natural materials and semi-precious stones. The Bohemian movement is the label of counter-culture rock stars and precocious fashionistas alike, one of many commercialised images of rebellion available to those who have the time and money to invest in cultivating it. If one takes a moment to dig a little deeper, however, it soon becomes apparent that—like so many motifs appropriated from disenfranchised groups—Bohemianism lies rooted in a rich and meaningful past. Moreover, its ethos carries a surprising relevance today.

The Origins Of The Bohemian Movement

Though it is little-realised today, we owe much of our modern perception of art and the artistic lifestyle to the French Revolution. During the 1700s, painters, musicians, and other creatives were not regarded with the same degree of reverence afforded by modern audiences. Instead, they were seen as simple tradespeople. They were there, like builders and tailors, to perform a service for the wealthy, painting their portraits, composing their waltzes, etc. According to Malcolm Easton, author of Artists and Writers in Paris: The Bohemian Idea, 1803-1867 they were regarded as belonging in ‘a place somewhere between the upper-domestic, and lower-civil, servant.’

Though it is little-realised today, we owe much of our modern perception of art and the artistic lifestyle to the French Revolution. During the 1700s, painters, musicians, and other creatives were not regarded with the same degree of reverence afforded by modern audiences. Instead, they were seen as simple tradespeople. They were there, like builders and tailors, to perform a service for the wealthy, painting their portraits, composing their waltzes, etc. According to Malcolm Easton, author of Artists and Writers in Paris: The Bohemian Idea, 1803-1867 they were regarded as belonging in ‘a place somewhere between the upper-domestic, and lower-civil, servant.’

Naturally, this subservient role left little time for actual creativity: Many artists were born into their ‘trade’ and relied wholly on the patronage of wealthy individuals to make a living. Aristocrats could therefore dictate what sort of subject matter it was acceptable for artists to represent in their work—and they did. Artists were typically seen as vulgar, uneducated individuals; mere vessels through which the visions of aristocrats could be made manifest.

It was partly due to this second-class status that artists became associated with a confluence of socioeconomic and political factors that were in a state of flux in France at the time. Frustrated with the cold rationality that had risen from the Age of Enlightenment—the idea that nature, in all her splendour, can be explained away by man—and the destructive influence of the bourgeoisie-driven Industrial Revolution, many writers (and other cultural influencers) were calling for a return to freedom, feeling, and the wholehearted embrace of the spirit. Dubbed Romantics, writers and artists like Balzac, Blake, and Hugo began to champion the value of intuition and emotion over rationalism in defining both the arts and the human experience. In this endeavour, they elevated artists to heroes in the popular imagination—staunch individualists who, like the writers, were capable of fighting back against the hypocrisy and greed of the bourgeoisie.

The use of the term ‘Bohemian’ to describe this new breed of romantic, liberal vagabond began when French writers chose to associate the ‘free and easy’ lifestyle of the ‘merry poor’ with the nomadic Roma people, who were then believed to have originated from Bohemia, in central Europe. As the moniker gained momentum, however, writers like Henry Murger—whose famous work Scenes de la Vie de Boheme brought the word Bohemian into the public consciousness—made a great effort to distance their subjects from the much-maligned ‘gypsies’ of central Europe. Writing in the preface to his book, Murger stated that ‘The Bohemians of whom it is a question in this book have no connection with the Bohemians whom melodramatists have rendered synonymous with robbers and assassins. Neither are they recruited from among the dancing-bear leaders, sword swallowers, gilt watch-guard venders, street lottery keepers, and a thousand other vague and mysterious professionals whose main business is to have no business at all, and who are always ready to turn their hands to anything except good.’ Murger et al were quick to establish the idea that this new breed of artistic outsider was, if not noble, at least operating with a sense of higher purpose—pursuing, as the Bohemian mantra proclaims, ‘Truth, Beauty, Freedom, and Love’ above all else.

From this humble beginning in 19th century Paris, the Bohemian Movement spread outward rapidly, soon reaching the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Britain and helping to spawn the decadent, morally ambiguous aesthetic movement of the late 19th Century. By the turn of the century, a Bohemian was not seen as just an artist, writer, or musician who had shrugged off the tradition of serving the upper class in order to pursue a romantic vision; the term was also synonymous with a rejection of social mores. Bohemians were avowed Libertines who indulged their senses freely, eschewing conventional morality for a life of intoxication and a decidedly modern approach to sexuality.

From this humble beginning in 19th century Paris, the Bohemian Movement spread outward rapidly, soon reaching the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Britain and helping to spawn the decadent, morally ambiguous aesthetic movement of the late 19th Century. By the turn of the century, a Bohemian was not seen as just an artist, writer, or musician who had shrugged off the tradition of serving the upper class in order to pursue a romantic vision; the term was also synonymous with a rejection of social mores. Bohemians were avowed Libertines who indulged their senses freely, eschewing conventional morality for a life of intoxication and a decidedly modern approach to sexuality.

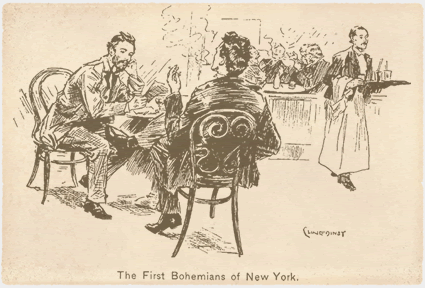

It was this milieu that gave rise to novels like George Du Maurier’s Trilby, a wildly popular book that depicted an eclectic and idealised group of young Bohemians in Paris. This novel achieved a reach significant enough to extend the notion of Bohemianism across the pond; Trilby greatly ‘affected the habits of American youth, particularly young women, who derived from it the courage to call themselves artists and “bachelor girls,” to smoke cigarettes and drink Chianti.’ (Luc Sante) This, naturally, helped to usher in the social revolution of the American Jazz Age in the 1920s.

The concept of Bohemianism remained a cultural fixture throughout the early 20th century, being taken up by each new wave of ‘down and out’ young artists and writers, most notably those of the Beat Generation (Jack Kerouac, William S Burroughs, and Paul Bowles). Even playwright Arthur Miller conjures up images of late American Bohemia with his descriptions of Manhattan’s Chelsea Hotel, a beloved haunt of artists, musicians, and writers where ‘there are no vacuum cleaners, no rules and shame’. Alas, as the 1960s swept away much of the conventionally staid middle-and-upper class way of life that Bohemianism had been a reaction to, the Bohemian Movement itself began to meld into obscurity. Bohemianism ultimately became mainstream—full of its characteristic decadence but empty of its social and creative purpose.

A New Dawn: Enter The Digital Bohemians

Perhaps somewhat ironically given the fact that the Bohemian Movement was rooted partly in a rejection of mechanisation, the Digital Revolution is actively reshaping and reinvigorating what it means to be Bohemian. With the rise of the ‘solopreneur’ (an entrepreneur who works alone with the intention of remaining small and independent, rather than growing and eventually being bought out) and the Digital Nomad (a solopreneur who leverages wireless technology to work while travelling freely), the widespread rejection of established systems and cultural norms is once again underway.

Where, just decades ago, most creative individuals had to pursue higher education and permanent employment with a large (and often creatively restrictive) firm in order to make a living, today these cumbersome middlemen are increasingly being cut out. Imaginative individuals of all stripes are increasingly using the internet and savvy self-marketing to connect themselves directly with freelance opportunities. Though many Digital Nomads are effectively homeless, they are not unwillingly so; as cited in the European Journal of Communication report The Changing Urban Landscapes of Media Consumption and Production, it is most often a ‘lifestyle choice of freedom over security and independence over regular income.’

There is, of course, more driving this revolution than mere fancy: Just as the Romantic artists and writers fought back against an oppressive system in a time of great political upheaval, today’s Digital Nomads are in essence rejecting an unsustainable, imbalanced model. In an uncertain and economically hostile world where affording a conventional ‘settled’ lifestyle is often out of the question regardless, they are by necessity drawing on their creativity (be it in the arts or some other area of innovation) to survive. They are rejecting the institutions of the elites—expensive colleges and multinational corporations—and forging their own paths, mirroring the Bohemians of old.

Walking in the footsteps of their Victorian predecessors, today’s mobile Bohemians are finding their way into books romanticising their way of life and worrying the establishment with their apparent imprudence. They are thinking, working, living, and loving with a broader, freer, outlook than their forebears. What change they will set in motion is anyone’s guess.