Bauhaus was an artistic movement that embraced design in many of its multifarious forms. Although today closely associated with architecture, it was an attempt to connect all forms of art and design through the social fusion of art with life.

The movement was founded by German architect Walter Gropius in 1919 in Weimar with the idea of unifying all art and design into one ‘total’ school of art. The school was created when Gropius was appointed to head two art schools and united them. He coined the term ‘Bauhaus’ by inverting the word for house construction, ‘Hausbau’, which was taken to mean ‘School of Building.’

Oddly enough, although Bauhaus today is a well-known formal architectural style, there wasn’t even an architectural department at the school until the late 1920s.

In the Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919), Gropius outlined how he envisaged a utopian guild that combined architecture, sculpture, and painting into one single artistic expression. His idea was to train artisans and designers to produce useful and beautiful objects that were a visual expression of the new Hausian style and could easily be mass-produced.

The focus on mass production sat somewhat awkwardly with the spirit of individual craftsmanship, but Gropius refocused the school through the slogan “Art into Industry.”

This was the time when it began to move away from creating private luxury and looked towards a more socially responsible, egalitarian approach to art and design.

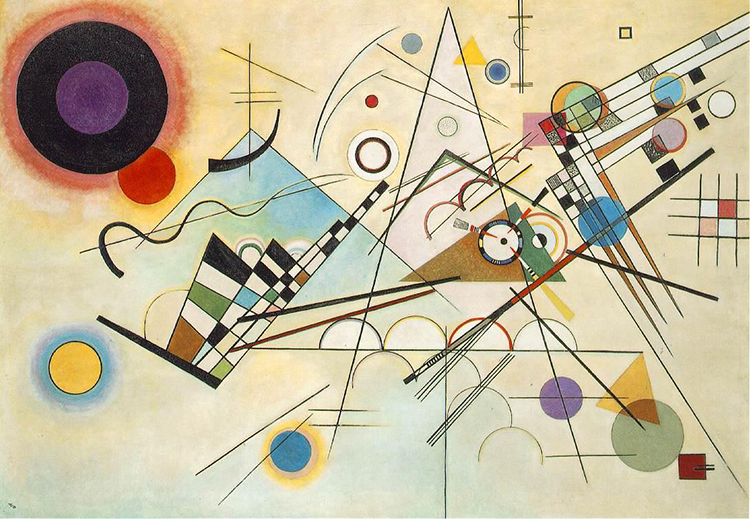

The true power of the movement was the ability of artists to cross long-held boundaries and find collaborators for mixed media art projects. It tore down the walls between the diverse branches and created a Brave New World where forms of expression became borderless, inclusive and universal.

That said, there was an inner core of Bauhaus, which had a clear agenda and fixed style that artists were expected to work within.

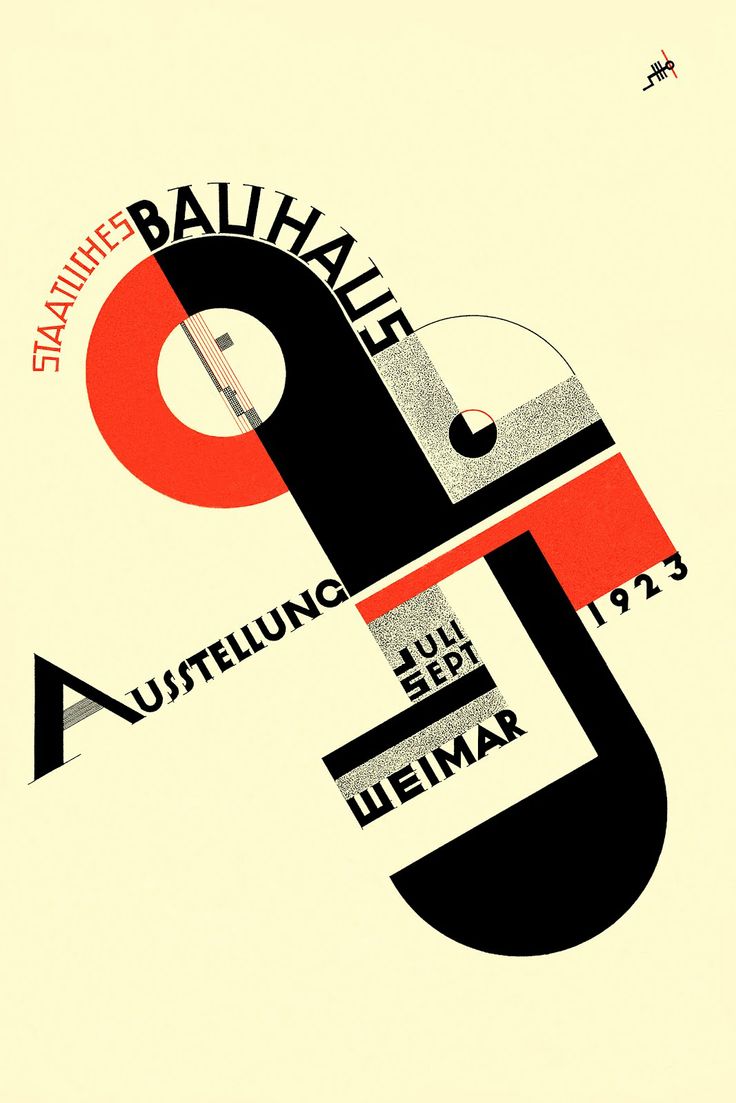

Students from all walks of life came to study the Hausian style, which was characterised by lean geometric patterns, a theory of colour, and a healthy respect for materials. Once immersed in Bauhaus theory, the students would then specialise in pottery, metalwork, furniture-making, cabinetmaking, wall painting, weaving, and pottery.

The school was hugely controversial and unpopular with Wiemar right-wingers who felt that the new style was ‘un-German. Due to the constant right-wing pressure, the school was moved to Dessau in 1925, where Gropius designed a new school building. It contained all the hallmarks of modernist architecture, such as an asymmetrical, pinwheel plan, steel-frame construction, and glass curtain walls.

Bauhaus teachers included such illustrious names as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lyonel Feininger, Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer.

At the school, typography became increasingly important and was considered both an art form and a means of communication. This duality meant typography became increasingly connected to advertising and as a means of representing corporate identity. All the promotional material produced at the Bauhaus mixed sans-serif fonts and graphic design to create the unmistakable look of this avant-garde institution.

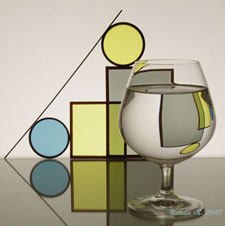

The metalworking and cabinetmaking studios were hugely successful in developing mass-production design prototypes. Designers such as Wilhelm Wagenfeld created beautiful, ultra-modern items, and he later went on to produce some typical Bauhaus-inspired glass art pieces.

In 1928, Gropius was succeeded as Bauhaus Director by the architect Hannes Meyer, who kept the emphasis on mass production but moved away from private luxury to more socially aware architectural design.

In 1930, Meyer resigned as director and was replaced by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who continued to emphasise architecture strongly.

With an increasingly unstable political situation in Germany and the impoverished financial situation of the school, it moved to Berlin in 1932, where it was closed the following year by the Nazis. The Nazis claimed it was a hotbed of communist intellectualism.

Many teachers, including founding father Walter Gropius, moved to America, where they influenced future generations of artists and designers. Gropius went to Harvard to teach, and Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer went to Yale, while Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937.

The far-reaching influence of Bauhaus is staggering, and the modern world is unimaginable without it. It has left a lasting legacy on British architecture, art, furniture, weaving, and even typography, and its echoes can still be felt to this day.

Further Reading:

Bauhaus. Updated Edition – by Magdalena Droste – Buy It HERE

The ABC’s of Triangle, Square, Circle: The Bauhaus and Design Theory – Illustrated – by Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller – Buy it HERE

Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus – by Fiona MacCarthy – Buy it HERE

Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography – by Magnus Englund and Leyla Daybelge – Buy it HERE

Gropius Hardcover – Illustrated – by Gilbert Lupfer and Paul Sigel, TASCHEN Peter Gössel (Editor) – Buy it HERE

Walter Gropius: Buildings and Projects – by Carsten Krohn – Buy it HERE

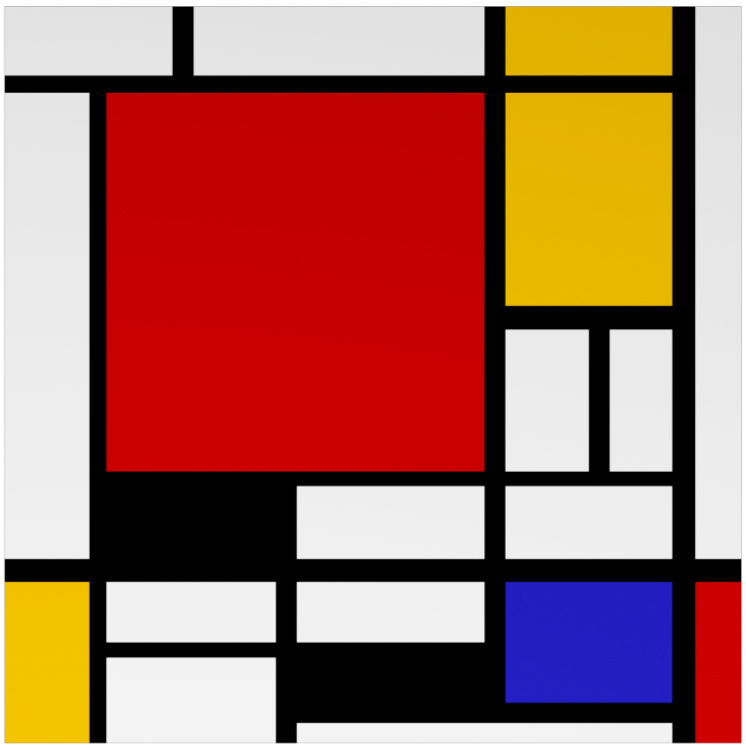

*a lot of these images are De Stijl.

Hi Emmett. Although Piet Mondrian was essentially Neoplasticism / De Stijl, he is often mentioned in connection with Bauhaus and was a major influencer.