Salvador Ysart, patriarch of the famous Ysart clan of Scottish art glass makers, was born Salvador Isart in Barcelona, Spain, on the 30th of January in 1875. While Salvador was the son of a glassmaker (it was actually his mother, not his father, who worked with glass—she was employed in finishing glass pieces), he did not start his working life in the trade. Little Salvador was a baker, and only turned to making glass when he found his baking career unsatisfying.

His beginnings as an art glass maker were decidedly humble; Salvador reportedly sneaked off behind his parents’ back and took a job at a local glass factory before he was ten years old, quite against the wishes of his father. The name of the factory and details of the time he spent there have, alas, been lost to history, but we do know that in 1909, the young man made his way to France, having been lured there by Emile Gallé’s ‘School of Nancy’ (this may have been yet another rebellious move on Salvador’s part; some say that he was driven away from Spain by the rigidly traditional nature of the glassmaking industry there, which left little room for individual expression). The school, which was devoted to Art Nouveau, had become something of a magnet to the artists, designers, and manufacturers of the day, and as such, would go on to have a major impact on the art glass industry.

By this time, Salvador was married, and had three young sons (he was to have a fourth after the family settled in Lyons for a brief period). Glass-making led to a nomadic life for the Isarts; they moved from town to town in France as Salvador made his mark on the nation’s various glassworks. Once again, details regarding this portion of Salvador’s life are rather scant, though it is known that he worked at Cristallerie Baccarat and Schneider Fréres et Wolf and that the family’s last move within France likely saw them reside in Choisy-le-Roi on the Seine, about six miles from Paris. It has also been hypothesised—but never confirmed—that Salvador worked at Legras & Cie at some point in time.

Salvador’s move to the UK arose from his experience at Schneider’s, which had been heavily investing in producing light bulbs, and also the impact of the first World War. World War One created a great many challenges for various British industries, as so many skilled workers were sent off to fight—many of them never to return—leaving a rapidly dwindling pool of talent to draw from within the UK. A lack of artisans during this era was nothing short of a crisis, as so many necessities which are today crafted by machine were then crafted by hand; ergo, special agents were dispatched from British factories to scour Europe for potential replacement workers.

As machines to create light bulbs would not be invented until the 1920s, the rapidly-growing electric light industry was one of the most desperate of all for new workers. Electric lighting was not merely a household pleasure during the war, it was also a strategic advantage, so glass blowers were among the most valued artisans sought out by factory agents.

Salvador’s glass-blowing skills were impressive enough that he was recruited to help train glassblowers to meet this great demand; becoming a Senior Glassblower for the Leith Flint Glass Company in Edinburgh, Scotland. (This company actually still exists in Scotland today, under the name of Jenkinson’s.)

It was during the immigration process that Salvador became known as Salvador Ysart, rather than Isart—he and his family’s names were anglicised, though the reason why remains unclear. It was perhaps done deliberately (for easier pronunciation), but it may have simply been a mistake on the part of the immigration officials; the Ysart family’s English was apparently still quite poor at this time.

After a tenure spent at the Leith Flint Glass Company, Salvador and his son Paul Ysart (who would later rise to great fame as an art glass maker himself, thanks to his incredibly detailed paperweight creations) joined A & R Cochran Limited, at St. Rollox Glassworks in Glasgow. Both father and son worked there until the factory closed down. They then bounced between a few other Scottish glassworks until 1922, when they were hired on by Moncrieff’s; Salvador as a Master Glassmaker, and Paul as a formal apprentice. Salvador and Paul would, in time, be joined at Moncrieff’s by two more of the Ysart boys: Vincent and Augustine.

Salvador’s fourth son, Antoine, was tragically lost to the family before he was able to join their ranks as one of Scotland’s great art glass makers; in 1942, he was knocked off his bicycle by two young people who unexpectedly emerged from a side street in Scone, near Perth, during the blackout. Antoine hit his head on a kerbstone as he fell; the blow was a severe one, and he passed away in the hospital several days later.

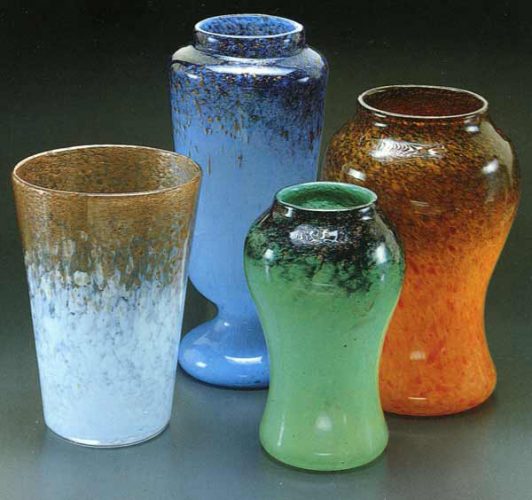

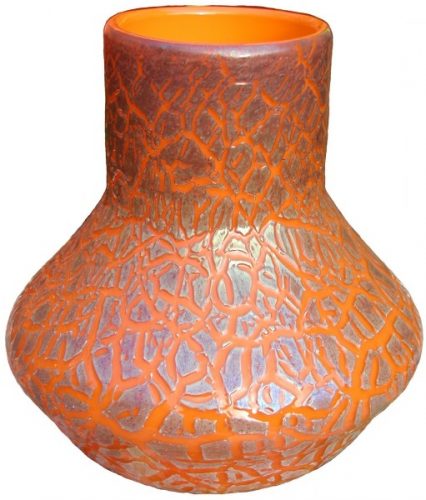

The four remaining Ysarts went on to create glass art that proved hugely popular and made the Ysarts well-known names within the industry and well beyond.

The legacy of Ysart Glass is still popular and pervasive today and many collectors of Ysart Glass seek out these rare gems at antique fairs around the country.