The history of Art Deco glass designs begins in the early twentieth century. The year was 1925: The hardships of World War One had given way to a burst of prosperity, stifling Victorian dress had been relegated to the attic in favour of loose, comfortable clothing, and along once-quiet country lanes the roaring of engines could be heard for the first time. Around the world, youth culture had begun in earnest: With young men happy to be alive and young women emerging into the light of liberty, a chaotic whirlwind of jazz music, motion pictures, and cocktail parties—the first to involve both sexes—were creating a kind of extended childhood for the flapper generation. Even art had burst forth from its cage: Owing to the advent of the camera, painters no longer had to concern themselves primarily with recording observable reality, and the brave minds of artists like Picasso were therefore reshaping our expectations of art.

The history of Art Deco glass designs begins in the early twentieth century. The year was 1925: The hardships of World War One had given way to a burst of prosperity, stifling Victorian dress had been relegated to the attic in favour of loose, comfortable clothing, and along once-quiet country lanes the roaring of engines could be heard for the first time. Around the world, youth culture had begun in earnest: With young men happy to be alive and young women emerging into the light of liberty, a chaotic whirlwind of jazz music, motion pictures, and cocktail parties—the first to involve both sexes—were creating a kind of extended childhood for the flapper generation. Even art had burst forth from its cage: Owing to the advent of the camera, painters no longer had to concern themselves primarily with recording observable reality, and the brave minds of artists like Picasso were therefore reshaping our expectations of art.

In Paris, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes—an enormous state-sponsored fair that ran for seven months and awed an estimated 16 million visitors while exhibiting everything from architecture and interior design to jewellery and perfumes—showcased the attempts of the design world to keep pace with all of this rapid change. Feeling threatened by the disillusionment surrounding the Art Nouveau movement (which had suffered from an influx of poor-quality wares after the year 1900) and the success of stripped-down, utilitarian German and Austrian design and manufacturing, the French were determined to use the Exposition to once again position themselves as a world leader in the luxury trades. What it revealed, however, was something far more important than the relative quality of French goods: The Exposition, which forbid the inclusion of any style not thoroughly ‘modern’, uncovered a remarkable aesthetic similarity in the works being displayed by the 20 participatory nations present. Somewhere between the end of the first world war and the dawn of the Jazz Age, Art Nouveau had organically transformed into a more accurate reflection of the times: Art Deco, a unique fusion of natural and mechanical motifs, geometric shapes, bold colours, and modern materials, had been born.

In Paris, the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes—an enormous state-sponsored fair that ran for seven months and awed an estimated 16 million visitors while exhibiting everything from architecture and interior design to jewellery and perfumes—showcased the attempts of the design world to keep pace with all of this rapid change. Feeling threatened by the disillusionment surrounding the Art Nouveau movement (which had suffered from an influx of poor-quality wares after the year 1900) and the success of stripped-down, utilitarian German and Austrian design and manufacturing, the French were determined to use the Exposition to once again position themselves as a world leader in the luxury trades. What it revealed, however, was something far more important than the relative quality of French goods: The Exposition, which forbid the inclusion of any style not thoroughly ‘modern’, uncovered a remarkable aesthetic similarity in the works being displayed by the 20 participatory nations present. Somewhere between the end of the first world war and the dawn of the Jazz Age, Art Nouveau had organically transformed into a more accurate reflection of the times: Art Deco, a unique fusion of natural and mechanical motifs, geometric shapes, bold colours, and modern materials, had been born.

Diverse and inventive from its inception, Art Deco became so stylistically broad during its reign that the phrase ‘Art Deco’ has been accused of being a catch-all term in grave need of refinement. There is, however, no questioning its overall success: The popularity of the Exhibition ensured that unlike Art Nouveau, Art Deco was a commercial hit the world over, transforming and adapting to its surroundings as it spread from one continent to the next.

Capturing The Spirit Of Change: The Impact Of Art Deco On Architecture And Design

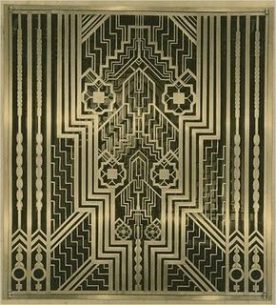

Today, Art Deco is perhaps best remembered for its buildings; both interiors and exteriors fashioned in this style show an awe-inspiring attention to detail. In America in particular, “Buildings were richly embellished with hard-edged, low-relief designs: geometric shapes, including chevrons and ziggurats and stylised floral and sunrise patterns. Shapes and decorations inspired by Native American artwork were [also] among the archetypes of the Art Deco lexicon.” (Wentworth)

Today, Art Deco is perhaps best remembered for its buildings; both interiors and exteriors fashioned in this style show an awe-inspiring attention to detail. In America in particular, “Buildings were richly embellished with hard-edged, low-relief designs: geometric shapes, including chevrons and ziggurats and stylised floral and sunrise patterns. Shapes and decorations inspired by Native American artwork were [also] among the archetypes of the Art Deco lexicon.” (Wentworth)

In addition to geometric patterns, some of the major themes present in Art Deco architecture and design include:

Nationalism: From early Soviet-era propaganda posters to the Eastern Airlines building (circa 1939) in the United States, patriotic symbols featured heavily in Art Deco art and ornamentation. This is likely due to a confluence of factors: Emerging from the first world war, many nations were forging (and re-forging) their individual identities; additionally, the nationalistic focus of the Paris Exposition (with its competitive wares from a multitude of different nations) likely helped to set the tone for the era.

Mythology: For all that Art Deco was considered a thoroughly ‘modern’ movement, in its expression of the power of manufacturing and emergent technology it frequently looked to the ancient past for inspiration. Figures from myth were often used to symbolise a building’s connection to the industry that occupied it, conceptualising corporations as the almighty entities of the age. Curiously, this penchant for industrial grandiosity only increased as the Great Depression wore on, as though society at large was desperately clinging to the dream of deified modernity that had so influenced the affluent 1920s.

Murals and Glasswork: Art Deco glass designs were often at their best in the bold, vivid stained glass ‘picture windows’ of the period; freed from the overly-intricate, ‘fussy’ styles of yesteryear, Art Deco glass designs clearly depicted scenes featuring sunbursts, hills, water (and ships), trees and other botanical features, people, etc., often with painted detail work for emphasis. (For an extensive look at Art Deco glass designs within the home, see our articles on Steuben glass, Vaseline glass, Czech art glass, and Depression glass.)

Architects also used “iconic sculptures, bas-reliefs and murals to exude what the building represented,” according to Wentworth Studios, “Public buildings had icons which told stories of the past or represented the glory of modernity. Private enterprises turned ephemeral goods such as railroad car wheels into decoration defining the period’s increasing speed and reliance on technology.”

Metalwork: Just as elaborate Art Deco glass designs were made affordable by more efficient industrial practices, so too was advanced metalwork brought to the masses: Advances in metallurgy made alloys more economical and therefore employable on a large scale, resulting in a proliferation of aluminium, stainless steel, and bronze elements throughout Art Deco structures. Everything from cornices to elevator doors, light stanchions, sculptures and radiator covers were crafted from gleaming metals.

Metalwork: Just as elaborate Art Deco glass designs were made affordable by more efficient industrial practices, so too was advanced metalwork brought to the masses: Advances in metallurgy made alloys more economical and therefore employable on a large scale, resulting in a proliferation of aluminium, stainless steel, and bronze elements throughout Art Deco structures. Everything from cornices to elevator doors, light stanchions, sculptures and radiator covers were crafted from gleaming metals.

With its blend of mechanical and botanical motifs, use of mythological characters and national symbols, and wholehearted embrace of both robust materials and lavish ornamentation, the Art Deco movement represents a unique transitional period between our pre-industrial past and technological present. For a brief time—before pride in quality craftmanship gave way to the mid-century Postwar emphasis on cheap building materials and inexpensive, mass-produced commodities—art and functionality combined, creating monuments to the sinuous beauty of power and the enduring glory of civilisation.