When studying antique art glass, it’s easy to get caught up in the grandiosity of it all—towering stained glass windows shattering the sun into a thousand colours, tall vases which swirl with galactic patterns, and great bowls and platters adorned with intricate scenes and figures that hold all the grace of the classical age.

There is, however, great value to be found in studying (and collecting) smaller antique art glass items as well. We can learn as much, if not more, about the role and importance of glass in society by examining the little pieces, the common pieces which touched the everyday lives of millions.

There is, however, great value to be found in studying (and collecting) smaller antique art glass items as well. We can learn as much, if not more, about the role and importance of glass in society by examining the little pieces, the common pieces which touched the everyday lives of millions.

While they are diminutive, Bohemian glass buttons—like most forms of early and mid-20th century Czech glass—display a remarkable degree of care and artistry. Almost all of these buttons were handmade (save those very plain and small types, which could be moulded automatically via machine), requiring a keen eye, steady hand, and a passion for detail.

The Bohemian craftsmen of that era typically worked at individual stations which revolved around a small furnace; they were given a quantity of glass canes and button moulds which allowed them to produce buttons only one at a time by hand-pressing semi-molten glass cane. One can only imagine how hard these dedicated professionals had to work to meet the demand that existed at the time; prior to the prevalence of plastic, most buttons were made of glass, and the majority of the glass buttons produced during the 20th century can trace their origins back to Czechoslovakia. Likewise, the industry was forever adapting to the whims of fashion, so Bohemian button makers found themselves having to constantly update their techniques to reflect the current trends.

Owing to the ephemeral natural of fashion, and the impact of World War II and the Cold War on the region, Bohemian glass buttons are fairly easily dated and categorised—a boon to collectors today. Due to this ease of classification, their relative inexpensiveness as compared to other forms of antique art glass, and the fact that even an extensive button collection takes up only a small amount of space, Bohemian glass buttons are ideal for those who might otherwise steer clear of art glass collecting due to a lack of space or funds.

The Early Years of Czech Button-Making: 1800-1945

While Europe had been “button crazy” since the 13th century (enough so that the church once denounced buttons, calling them the “Devil’s snare”), prior to the Industrial Revolution, one had to be fairly wealthy in order to afford decorative glass buttons owing to how much time and skill it took to produce them.

Most of those early “heirloom” buttons were made in England and France, with button production beginning in earnest in the Czech lands only after the invention of the first button mould in the mid-1700s. These moulds—which allowed the “shank” of the button to be incorporated into it as it was pressed—revolutionised the button industry throughout Europe, and by 1890, the mostly cottage-based glassmakers based in the Jablonec nad Nisou region were making buttons by the thousands.

In 1918, as the Austrian empire collapsed, Germans bought many of the glassworks in Bohemia, and the region (which they dubbed “Gablonz”) gained true recognition as the glass button and bead capital of the world, producing the following popular styles:

Pre-WWII: Painted Glass Pictorials

From the end of World War I until the start of World War II (1918-1939), buttons decorated with painted florals and cut crystal designs were highly popular, as were pictorial buttons actually shaped to resemble their subject matter (these are often called “realistics”). As the Art Deco movement rose to prominence, Bohemian buttons began to make use of Art Deco motifs as well.

From the end of World War I until the start of World War II (1918-1939), buttons decorated with painted florals and cut crystal designs were highly popular, as were pictorial buttons actually shaped to resemble their subject matter (these are often called “realistics”). As the Art Deco movement rose to prominence, Bohemian buttons began to make use of Art Deco motifs as well.

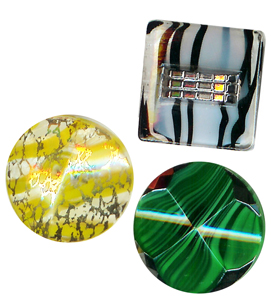

While many of these buttons are fairly basic in colouration, making use of standard black, white, clear crystal, and bold shades rendered in either opaque or transparent glass, more intricate styles from this period also exist. The latter tended to have either mixed colours (striped, spattered, or marbled) or delicate painted or fired-on decoration (gold and silver lustres were particularly popular).

In addition to many of the glasshouses in Bohemia being German-owned, much of Northern Bohemia was a traditionally German area, which set the stage for a great deal of fluctuation in the local industry over the years to come. In 1938, Germany occupied Czechoslovakia, taking full control of all of those glassworks not already owned by Germans.

World War II: Plain Glass Buttons

After the Germans seized Bohemia, they reduced all civilian glass production to bare necessities, preferring to focus all of their efforts on producing those glass items which were needed for military purposes (e.g. faceted glass lenses, which were used to cover instrument lights). Glass button-making did not, however, cease altogether—as brass was even more in demand than glass (it was used to make ammunition), exact copies of brass buttons were rendered in plain glass.

This was not the biggest hit to the Bohemian glass industry, mind you—that was to come in 1945, when the vast majority of the region’s German population was literally expelled overnight, given only 24 hours to evacuate. Most took only what they could carry, leaving all of their button manufacturing equipment (including precious moulds and glass stock) behind in Czechoslovakia.

As the German people of the region had traditionally been responsible for an appreciable portion of its glassmaking activity (stretching right back to the early middle ages), this had a profound impact on the Czech glass industry. Many of the great Bohemian glasshouses vanished with the cessation of World War II, or carried on only in a very hobbled capacity.

Thankfully, as the use of plastics was not yet widespread, the glass button industry picked up again after the war fairly successfully; it merely became divided, with one half of it continuing on in Germany rather than in the Czech Republic.

The Postwar Period: Black Glass with Lustres, Modern Realistics, and the Fabulous 50s

As Bohemia passed from German to Soviet hands in 1946, the glass industry moved away from being a true “cottage industry”. Button craftsmen were instead forced to work at large state-directed factories, with a single state-controlled company handling all exports. This would be the default model for glass production in Bohemia until 1988, when the “Velvet Revolution” finally ended the reign of the communist Soviets.

While one might assume this set-up would limit the button makers’ creativity, a surprising variety of button styles from this period exist. Some buttons were plain and modernistic, or appeared with politically-motivated designs, but there was still a delightful selection of “fabulous 50s” retro art glass designs, replete with every finish imaginable. These included:

While one might assume this set-up would limit the button makers’ creativity, a surprising variety of button styles from this period exist. Some buttons were plain and modernistic, or appeared with politically-motivated designs, but there was still a delightful selection of “fabulous 50s” retro art glass designs, replete with every finish imaginable. These included:

- Gold and silver lustres (which never truly lost their prior popularity), often placed over black glass

- Painted designs, also frequently applied to black glass

- Intermixed glass

- Glass “salt” (very small flecks of glass fired to the surface of a button)

- Decals and metal embellishments

- Designs cut into the surface of the glass

- “Moonglow” glass.

Moonglow glass buttons featured an opaque base under a clear glass top, making some of them similar to paperweights in appearance (others had extensive surface decoration).

Unlike in decades prior, when Bohemia had supplied much of Europe with glass items, during the Soviet era, most of its output was sold to other Soviet states, notably Eastern Bloc countries like Russia. As such, many carded Czech buttons from this era feature Cyrillic text.

Moonglow buttons were also made in Germany during the 1960s; prior to this only buttons with basic surface designs appear from German postwar craftsmen, as the expelled German glassmakers started their glassworks over from scratch, applying their existing knowledge to what resources they could find in Germany. By the 1960s, however, manufacturing capabilities began to align with pre-war levels, with over 400 individual companies manufacturing a variety of retro art glass buttons in Germany.

Moonglow buttons were also made in Germany during the 1960s; prior to this only buttons with basic surface designs appear from German postwar craftsmen, as the expelled German glassmakers started their glassworks over from scratch, applying their existing knowledge to what resources they could find in Germany. By the 1960s, however, manufacturing capabilities began to align with pre-war levels, with over 400 individual companies manufacturing a variety of retro art glass buttons in Germany.

German designs were held to a higher standard than their factory-produced Czech brethren at this point, and as such, they tend to exhibit a more restrained, professional, and couture-focussed style. Still, they focused on the same basic looks, with a range of intermixed designs, painted and lustred moonglow, and painted, plain, or lustred black glass.

Sadly, just as German button-making was reaching its zenith, automatic sewing machines and washing machines started to become widespread in their use. As glass is quite delicate, glass buttons did not survive this transition terribly well, and buttons intended for consumers were therefore increasingly made out of plastic and metal.

The late 1960s to the late 1990s: Aurora Borealis on Opaque Glass, the Resurgence of Czech Cottage Industry

As plastic became more and more prevalent, the range of retro art glass button designs decreased significantly, with moonglows and intermixed designs eventually dwindling into nonexistence. There was one major new development in the world of glass button-making, however: Intensely colorful fired-on iridescent lusters (dubbed “auroras” in the button trade) were developed, and experienced a brief period of intense popularity.

As plastic became more and more prevalent, the range of retro art glass button designs decreased significantly, with moonglows and intermixed designs eventually dwindling into nonexistence. There was one major new development in the world of glass button-making, however: Intensely colorful fired-on iridescent lusters (dubbed “auroras” in the button trade) were developed, and experienced a brief period of intense popularity.

In 1989, the fall of communism toppled the state-directed factory and distribution system, allowing Bohemian glassmakers to once again set up their own small businesses (many of which made use of molds and equipment obtained from the sprawling derelict state factories). By this time, the glass button industry was so small that most of the region’s production was focused on meeting special orders, usually from American collectors. At the same time, in Germany, much of the Old German glass stock was sold off in bulk to countries in the Middle East and Africa.

In addition to the decline in demand for glass buttons, stricter environmental regulations in Europe limited or banned the manufacture of most of the chemicals needed for many types of glass and glass finishes, particularly auroras and black moonglows, putting the final nail in the coffin of the German-Czech glass button-making industry.

Today, very few Czech and German glass button makers exist, and those that do sell only a very limited number of buttons (mostly to collectors and specialty retailers). Thankfully, these glassworkers do possess—and use—a variety of authentic mid-century moulds, so the art of the original Bohemian button-makers has not been entirely lost.

As literally millions of buttons were produced in Bohemia (and later Germany) during the industry’s heyday, modern collectors have an astounding variety of affordable handmade pieces to choose from. As such, for many collectors, Bohemian buttons provide one of the most shameless indulgences of the art glass world—a microcosm of glass art history which can be held in one’s hand.