Arts and Crafts Movement (c.1860 to 1910)

Arts and Crafts Movement (c.1860 to 1910)

The Arts and Crafts movement formed in the second half of the 19th century and was made up of English designers and writers who wanted a return to well-made, handcrafted goods instead of mass-produced, poor-quality machine-made items. In the 1890s the popularity of the Arts and Crafts movement widened. Its ideas quickly spread throughout Europe and became very popular in the USA, becoming identified with the growing international interest in design.

In Britain the movement was associated with dress reform, ruralism, the garden city movement and the folk-song revival; with 130 separate Arts and Crafts organisations identified (the majority formed in the creatively radical decade between 1895 and 1905). In continental Europe, it was more closely aligned with the preservation of national traditions in building, the applied arts, domestic design and costume.

Arts and Crafts style even emerged in Japan during the 1920s.

The motto for the Society of Designers in 1896 reads ‘Head, Hand and Heart’. This motto is a good way of understanding the ethos behind the movement. It was taken from an inscription by Charles Veysey and it simply means ‘Head’ for creativity and imagination, ‘Hand’ for skill and craft, and ‘Heart’ for honesty and for love. The Arts and Crafts Movement held at its core the idea that the handmade object was both beautiful and useful in everyday life. The objects fashioned were simple in form, without superfluous or excessive decoration, and you could often see how they had been constructed together. They have the principle of “truth to the material.” Oakwood was often used, as was copper and pewter.

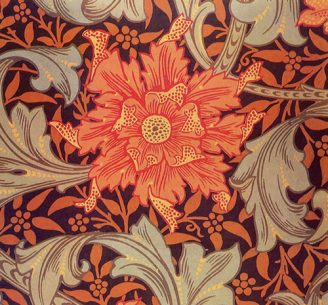

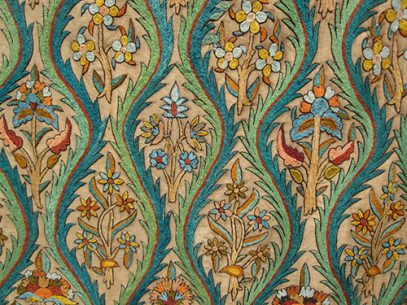

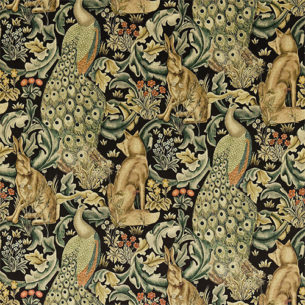

Makers often applied Gothic, romantic, folk, organic and natural motifs into stylised patterns. These patterns were often flowers, allegories from the bible and upside-down hearts. Visually, the style has much in common with its contemporary Art Nouveau and it played a role in the founding of Bauhaus and Modernism. Some of the influences behind this style were medieval styles – the Gothic revival led by AN Pugin, the Orient – the pared-down quality of Japanese art, and socialism – the ideas of John Ruskin and early Marx.

The aesthetic and social ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement also derived from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of the 1850s. The Brotherhood was formed by a group of friends at the University of Oxford, including William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and some of Burne-Jones’ associates from Birmingham at Pembroke College, who became known as the Birmingham Set. The Birmingham Set had first-hand experience of modern industrial society and combined their love of Romantic literature with a commitment to social reform. By 1855 they had come across the writings of John Ruskin and they formed themselves into the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to pursue their artistic and social goals.

The aesthetic and social ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement also derived from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of the 1850s. The Brotherhood was formed by a group of friends at the University of Oxford, including William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and some of Burne-Jones’ associates from Birmingham at Pembroke College, who became known as the Birmingham Set. The Birmingham Set had first-hand experience of modern industrial society and combined their love of Romantic literature with a commitment to social reform. By 1855 they had come across the writings of John Ruskin and they formed themselves into the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to pursue their artistic and social goals.

Inspired by socialist principles and led by William Morris, a poet, the members of the movement used the medieval system of trades and guilds to set up their own companies to sell their goods.

William Morris also set up his own company with fellow artists called Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co in 1861, (later just Morris & Co), which produced everything from furniture and textiles to wallpaper and jewellery. Also, William de Morgan (glass, tiles and pottery), CFA Voysey (wallpaper, textiles and silverware) and Richard Norman Shaw (architect).

We need to be aware this wasn’t just a style, it was a way of living founded on Utopian ideals. By the mid-nineteenth century, cheap factory-made goods had almost entirely driven away hand craftsmen and women from their trades. The old techniques of making well-crafted, elegant objects by hand were nearly lost. The Arts and Crafts Movement supported economic and social reforms as a way of attacking the industrialised age. Followers of the movement favoured craft production over industrial manufacturing and were troubled by the ethics and effects of the factory system on workers.

We need to be aware this wasn’t just a style, it was a way of living founded on Utopian ideals. By the mid-nineteenth century, cheap factory-made goods had almost entirely driven away hand craftsmen and women from their trades. The old techniques of making well-crafted, elegant objects by hand were nearly lost. The Arts and Crafts Movement supported economic and social reforms as a way of attacking the industrialised age. Followers of the movement favoured craft production over industrial manufacturing and were troubled by the ethics and effects of the factory system on workers.

By the early 1880s, Morris was spending more of his time on socialist propaganda than on designing and making, but many Art and Craft associations sprung up as the wider movement grew such as the Home Arts and Industries Association. This association was formed in 1881 by Eglantyne Louisa Jebb, Mary Fraser Tytler and others to encourage the working classes, especially those in rural areas, to take up handicrafts under supervision, not for profit, but in order to provide them with useful occupations and to improve their taste. By 1889 it had 450 classes, 1,000 teachers and 5,000 students. Other associations set up during this time such as The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, formed in 1887, and promoted embroidery, fabrics, upholstery and furniture.

The main controversy raised by the movement was its practicality in the modern world.

The main controversy raised by the movement was its practicality in the modern world.

The progressives claimed that the movement was trying to turn back the clock and that it would fail, that the Arts and Crafts movement could not work in a practical, mass urban and industrialised society.

On the other hand, a reviewer at the time who criticised an 1893 exhibition as “the work of a few for the few” also realised that it represented a graphic protest design as “a marketable affair, controlled by the salesmen and the advertiser, and at the mercy of every passing fashion.”

There are still many places where you can see examples of this movement. A few of these are:

Kelmscott House, London W6 – The William Morris Society’s HQ.

William Morris Gallery, London – where he lived, now a museum.

Leighton House Museum, London – Oriental and Aesthetic Interiors

Hampstead Garden Suburb and Bedford Park, London – built by Richard Norman Shaw

Standen, East Grinstead, West Sussex – decorated throughout in William Morris.

It is easy to just see this movement as a short moment in history, however, the traditions of handmade, and the demand for something unique, have never been so alive and well as they are in Britain today. The influence of this time has continued among craft makers, designers, and town planners to this day. Aided by the internet and exhibition platforms, craftsmen and women can sell their pieces directly to the public.

Further Reading

William Morris – V & A Museum – GET IT HERE

William Morris’s Flowers – Victoria and Albert Museum – GET IT HERE

William Morris: A Life for Our Time – by Fiona MacCarthy – GET IT HERE

The Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain – by Mary Greensted GET IT HERE

Women Pioneers of the Arts and Crafts Movement – Victoria and Albert Museum – by Karen Livingstone (Editor) – GET IT HERE