Beautiful Monsters: The Strange Appeal Of Brutalist Architecture

Around the world—and in Britain perhaps most poignantly—the 1950s and 1960s were a time of unparalleled optimism. These ‘years of hope’, as the late Tony Benn dubbed them, saw the middle class of the nation transformed by peace and prosperity. Wayland Young, in his book Return to Wigan Pier, summed up the mood of the era perfectly when he wrote that since Orwell had published The Road to Wigan Pier in 1937, Wigan had changed from ‘Barefoot malnutrition to nylon and television, from hollow idleness to flush contentment.’ As the postwar period reached its zenith with the advent of the space age, it seemed as though we had finally conquered the Earth and our future was to be found amongst the stars.

Around the world—and in Britain perhaps most poignantly—the 1950s and 1960s were a time of unparalleled optimism. These ‘years of hope’, as the late Tony Benn dubbed them, saw the middle class of the nation transformed by peace and prosperity. Wayland Young, in his book Return to Wigan Pier, summed up the mood of the era perfectly when he wrote that since Orwell had published The Road to Wigan Pier in 1937, Wigan had changed from ‘Barefoot malnutrition to nylon and television, from hollow idleness to flush contentment.’ As the postwar period reached its zenith with the advent of the space age, it seemed as though we had finally conquered the Earth and our future was to be found amongst the stars.

In a testament to mankind’s inherent penchant for contradiction—the same predilection that had cheery big band music booming across the airwaves as if to drown out the sound of air raid sirens a decade prior—it was into this blithe social climate that the architectural movement known as Brutalism was born. Lasting from roughly the 1950s to the mid-1970s, Brutalism would leave its mark on cities across Europe and North America, with the UK as its undeniable epicentre.

The Soul Of A Brute: Embracing A Misunderstood Style

Though many assume that the term ‘Brutalism’ refers directly to the imposing appearance of Brutalist structures, in reality the name is a bilingual pun based on the French ‘béton brut’ (‘raw concrete’). This defining trait—the use of rough, unfinished concrete—would become both the hallmark and the undoing of Brutalist buildings: Hallmark because, of course, it’s unmissable; undoing because this type of exterior is easily-stained and quickly-weathered, causing the majority of these structures to become what many would unabashedly call ‘an eyesore.’

Brutalism is not everyone’s cup of tea, it’s true, but it wasn’t meant to be. Brutalism is the visual voice of staunch opposition: It loudly refuses the lightness of ‘New Humanism’, the airy modernist style that leading Brutalist architects and architectural critics like Peter Smithson and Reyner Banham so avidly wished to banish from British suburbs and cityscapes. It’s a blunt rejection of nature and the antithesis of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, with their flowing curves and stylish, tapered geometry. Brutalist architecture does not even try to conform, and in this they embody the soul of mid-century optimism in spite of their rugged lines and sometimes oppressive mien: They are monuments to the idea that mankind can triumph over his surroundings. They are proof that even ugliness, when taken to monolithic extremes, has its own strange kind of beauty.

Towering Concrete, Complex Geometry, and Creative Glass: How To Recognise a Brutalist Building

The term ‘Brutalism’ is (as is standard where art and architectural movements are concerned) somewhat nebulous and difficult to absolutely define. While raw concrete is indicative of the style, it may also suggest Constructivism, International Style, Expressionism, Postmodernism, or Deconstructivism, so it’s important to take a closer look at a building before labelling it ‘Brutalist’. Generally, one should look for:

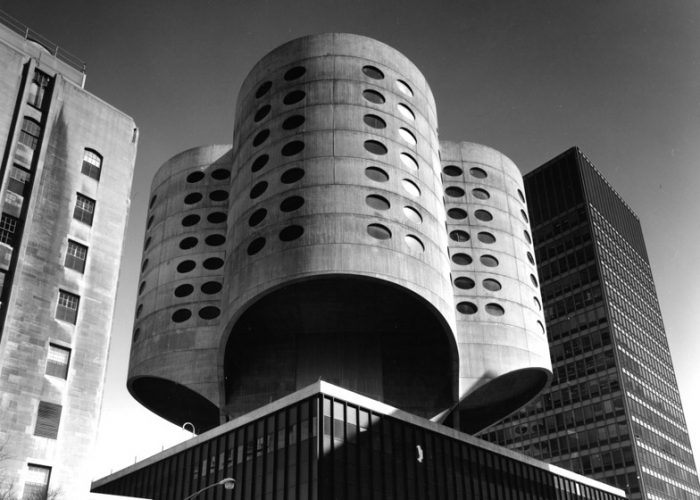

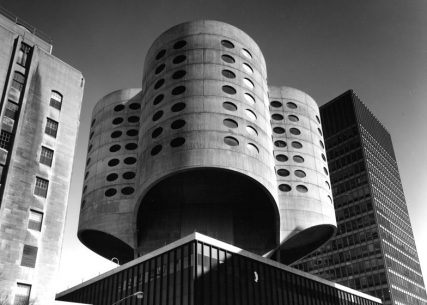

- A massive, monolithic style: Brutalist buildings are often (though not always) large and blocky in nature. Geometric shapes are frequently and imaginatively embraced, e.g. cubes placed atop cubes, rounded towers rising up unpredictably from robust buildings, and angles jutting out proudly. Brutalist styled buildings also tend to have a ‘top heavy’ look where the size of the upper part of the structure exceeds that of the lower part.

- Functionality, exposed: Many Brutalist buildings have exteriors which are designed to reflect their interior features (the more functional and unglamourous, the better). For example, Smithdon High School in Norfolk (completed in 1954) has purposefully revealed its water tank by placing it in an obvious, visible tower.

- Creative glass use: Brutalist buildings often take a ‘less is more’ approach to glass use. They reject the ubiquitous ‘glass wall’ that was taking over city structures during the middle of the 20th century and instead opt for windows that are either recessed into the surr

ounding concrete, patterned to complement the intricate outline of the structure itself, or that provide an engaging creative glass contrast which emphasises the building’s shape—for example, the Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, where small circular ‘porthole’ style windows both flatter the round central tower and oppose the hard rectangles of the rest of the building.

ounding concrete, patterned to complement the intricate outline of the structure itself, or that provide an engaging creative glass contrast which emphasises the building’s shape—for example, the Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, where small circular ‘porthole’ style windows both flatter the round central tower and oppose the hard rectangles of the rest of the building.

In the United Kingdom, look for buildings designed by architects such as Ernő Goldfinger, Alison and Peter Smithson, Sir Basil Spence, the LCC/GLC Architects Department, Owen Luder, and John Bancroft.

A Legacy Under Threat

Just as Britain’s charming mid-century nativity crumbled during the recession years of the 1970s, the extreme style of Brutalism has proved to be of impermanent substance. In addition to the weathering that raw concrete is prone to, many Brutalist buildings were constructed using inexpensive materials owing to the lingering scarcity caused by World War Two: After being destroyed on such an incomprehensible scale, the UK needed to rebuild as quickly and cheaply as possible. Sadly, this has resulted in Brutalist buildings being prone to leaks and mould issues that are costly to repair—leaving many a grand Brute slated for demolition.

Though it can be difficult for non-enthusiasts to see the merit in preserving these lumbering relics, Brutalist architecture remain an important part of our cultural heritage; like the British Bulldog, these no-nonsense buildings have become a statement of what it means to be English: Not always gentle, not always graceful, but most certainly indomitable. Too, they house a spirit which has since left the Western world: The perception of limitless horizons and inexhaustible resources, the happy ignorance of pollution, the expansiveness of a race that teetered on the brink of annihilation and somehow came out swinging.

Our aspirations as a species have, of course, since come back down to Earth; today we are rightfully more concerned with preserving and honouring the planet we have than we are with subjugating it while we venture on to brave new worlds. However, without these concrete behemoths to stand as testament to our mid-century dreams, ambitions, triumphs, and follies, will the hard-won lessons of the 20th century still be remembered decades from now, long after the ‘baby boomers’ have gone to explore that most final of frontiers? Just as a scar is usually attached to a story, no one can deny that these so-called marks of blight on the urban landscape have something to say about the society that built them.

If you’re interested in preserving Brutalist buildings, join the campaign at SOS Brutalism. If you want to discover London’s iconic Brutalist structures for yourself, check out the Brutalist Map of London.

ounding concrete, patterned to complement the intricate outline of the structure itself, or that provide an engaging

ounding concrete, patterned to complement the intricate outline of the structure itself, or that provide an engaging