While Asia is a continent much admired for its long history of artistic and technical achievement, ancient Asian glass craft has largely been overshadowed by more mainstream mediums; the popularity (both within Asia itself and amongst modern collectors) of Asian ceramic wares and metalwork has rendered glass something a footnote. However, though glassmaking got off to a comparatively late start in many parts of East Asia, by the advent of the Warring States era in China (475-221 BC), Chinese glass artists had begun to cease relying so heavily on imported glass owing to their desire to replicate the precious mineral, Jade. Centuries of experimentation with their own production methods, independent from the formulas used in Europe and the Middle East, resulted in the Chinese producing a type of glass unique both for its transparency and its role within society.

While Asia is a continent much admired for its long history of artistic and technical achievement, ancient Asian glass craft has largely been overshadowed by more mainstream mediums; the popularity (both within Asia itself and amongst modern collectors) of Asian ceramic wares and metalwork has rendered glass something a footnote. However, though glassmaking got off to a comparatively late start in many parts of East Asia, by the advent of the Warring States era in China (475-221 BC), Chinese glass artists had begun to cease relying so heavily on imported glass owing to their desire to replicate the precious mineral, Jade. Centuries of experimentation with their own production methods, independent from the formulas used in Europe and the Middle East, resulted in the Chinese producing a type of glass unique both for its transparency and its role within society.

A Fragile Beauty: Lead-Barium Glass

The earliest-known method of glass manufacturing in China, the alkali (generally potash) and lime glass system, soon gave way to the lead-barium system of glass production that characterised the Warring States period. While archaeologists are not entirely sure why the Chinese first chose to work with this formula, it is believed that the wide availability of both lead and barium and the fact that this composition lowered the melting point of the glass played a role. (As discussed in Early Manufacturing Techniques, the furnaces used in ancient times often struggled to produce enough heat to melt glass.) Produced in the Yangtze River valley region, lead-barium glass soon became very popular within China and was circulated throughout the more accessible areas of that vast country.

The choice to produce glass via the lead-barium system was instrumental in the largely ceremonial role glass played in ancient Chinese culture. However, lead-barium glass was incredibly clear as compared to most glass from this time period (soda-lime glass). It was also extremely fragile, making it suitable only for rendering art glass sculptures, beads, and other decorative objects. This delicacy was due to the extreme amounts of lead used (typically 10-45 per cent); high lead content increases the reflectivity of glass, giving it a more gem-like quality, but also results in a material which is far more brittle and heat sensitive than soda-lime glass.

The choice to produce glass via the lead-barium system was instrumental in the largely ceremonial role glass played in ancient Chinese culture. However, lead-barium glass was incredibly clear as compared to most glass from this time period (soda-lime glass). It was also extremely fragile, making it suitable only for rendering art glass sculptures, beads, and other decorative objects. This delicacy was due to the extreme amounts of lead used (typically 10-45 per cent); high lead content increases the reflectivity of glass, giving it a more gem-like quality, but also results in a material which is far more brittle and heat sensitive than soda-lime glass.

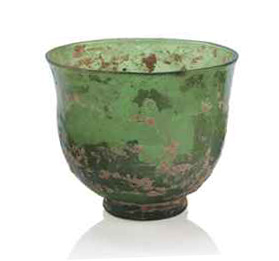

Archaeological evidence suggests that to the Chinese, the beauty of glass was more important than its function; a passage from the 5th century CE text Shishuo Xinyu (New Account of Tales of the World), for example, states that “The beauty of this [glass] cup lies in its transparency. For this reason, I consider it highly valuable.” Another text source from ancient China, Yen Fan Lu (1175 CE), corroborates these sentiments when comparing Chinese glass with Western glass: “The liuli [glass] which is made in China is rather different from that which comes from abroad. The Chinese variety is bright and sparkling, and the material is light but fragile. If you pour hot wine into it, it will immediately break. That which is brought by sea is rather rough and unrefined, and the colour is also slightly darker. But the strange thing is that even if hot water is poured into it a hundred times, it behaves like porcelain or silver and will never break.”

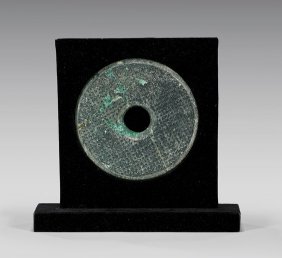

The well-developed pottery technology of the Chinese during the Warring States period (and the Han Dynasty epoch to follow) allowed them to dedicate their glassworks exclusively to producing imitation gemstone decorative and ceremonial wares. The most common objects made from the lead-barium glass during this era were beads, jewellery pieces, sword parts, and ritual Bi disks (disk-shaped art glass sculptures included in burials), with all of these items being made to resemble their mineral-based counterparts. The majority of the glass items from this period that remain intact today are beads, with “dragonfly eye” glass beads being the most celebrated. Ceremonial vessels such as cups and bowls have also been uncovered by archaeologists, but sadly, owing to the delicate nature of lead-barium glass, few large vessels have remained intact.

According to Early Chinese Lead-Barium Glass by Christopher F. Kim, imitating Jade was of the utmost importance during this period. “Even more than crystal, lapis lazuli, or turquoise, however, by far the most widespread use of lead-barium glass in early China was as imitation jade, a stone more precious than any other to the ancient Chinese. Jade had a number of symbolic and magical properties, including a close association with immortality. Daoist alchemists believed that jade, along with gold, was the antithesis of decay because it did not corrode (Hill 2009:260). Due to these symbolic properties, jade was often buried in tombs to safeguard the dead, a practice that began in Neolithic times but proliferated particularly in the Western Han period. (Braghin 2002b:22)” For the common person in ancient China, glass, therefore, served a sacred role; unable to afford costly Jade Bi disks, Chinese peasants relied on the lead-barium glass to safeguard their passages into Heaven.

While the doughnut-like shape of these early art glass sculptures may appear simplistic at first glance, it was highly culturally significant: Just as the Sun Cults of Egypt and Scandinavia used glass to help capture the magic of life-giving light (as described in Coloured Glass: Before The Age of Glass Blowing), the ancient Chinese Bi disks were given this disk-like shape so as to better represent the sun. (At the time, the Chinese character for “sun” was a disk, and it was also used to represent Heaven). During the Warring States period and the Han Dynasty, countless Chinese families laid their loved ones to rest on a bed of Jade-coloured glass Bi disks, feeling secure in the knowledge that poverty was no obstacle to spiritual transcendence and trusting in the power of the sun to deliver immortality.

While the doughnut-like shape of these early art glass sculptures may appear simplistic at first glance, it was highly culturally significant: Just as the Sun Cults of Egypt and Scandinavia used glass to help capture the magic of life-giving light (as described in Coloured Glass: Before The Age of Glass Blowing), the ancient Chinese Bi disks were given this disk-like shape so as to better represent the sun. (At the time, the Chinese character for “sun” was a disk, and it was also used to represent Heaven). During the Warring States period and the Han Dynasty, countless Chinese families laid their loved ones to rest on a bed of Jade-coloured glass Bi disks, feeling secure in the knowledge that poverty was no obstacle to spiritual transcendence and trusting in the power of the sun to deliver immortality.

The aforementioned practice continued until just after the fall of the Han Dynasty when Emperor Wen of Wei (187-226 CE) made it illegal to bury the dead with Jade; this decision diminished the cultural significance of Jade and thus its glass counterparts. Lead-barium glass as a whole seems to have waned in popularity as a result, and for a time, the role of glass in Chinese culture slumbered. Fortunately, however, the mysterious lustre of lead was not forgotten; high-lead glass would make a comeback during the Tang Dynasty, this time without the additive of barium. Additionally, artefacts from the Warring States period and the Han Dynasty would eventually go on to inspire the development of Liuli Crystal, a marvellously colourful glass from which highly sought-after art glass sculptures are made today.

I have this described folding screen was often decorated with beautiful art; major themes included mythology, scenes of palace life, and nature. It is often associated with intrigue and romance in Chinese literature, for example, a young lady in love could take a curious peek hidden from behind a folding screen.[1][2] An example of such a thematic occurrence of the folding screen is in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin.[5] The folding screen was a recurring element in Tang literature.[6] The Tang poet Li He (790–816) wrote the “Song of the Screen” (屛風曲), describing a folding screen of a newly-wed couple.[6] The folding screen surrounded the bed of the young couple, its twelve panels were adorned with butterflies alighted on China pink flowers (an allusion to lovers), and had silver hinges resembling glass coins.[6] I can send photos as this is really really old.

It sounds amazing! Please do send some photos and I will upload them. Thanks!