The freedom of spirit and expression that is immediately called to mind when one hears the word “Bohemia”—gipsies traipsing through wild lands in colourful dress, eschewing the trappings of money and classism to embrace music and adventure—is a natural fit with the principles of Art Nouveau, which championed a return to nature in its embrace of the shapes, imagery, and materials found in the natural world, and whose early champions, such as Les Vingt, saw their work “as a vehicle for social reform… to break down the barriers between so-called high art (painting and sculpture) and the applied arts (craft) to create a unified aesthetic that would be spiritually uplifting to people of all classes.” (Collector’s Weekly)

The freedom of spirit and expression that is immediately called to mind when one hears the word “Bohemia”—gipsies traipsing through wild lands in colourful dress, eschewing the trappings of money and classism to embrace music and adventure—is a natural fit with the principles of Art Nouveau, which championed a return to nature in its embrace of the shapes, imagery, and materials found in the natural world, and whose early champions, such as Les Vingt, saw their work “as a vehicle for social reform… to break down the barriers between so-called high art (painting and sculpture) and the applied arts (craft) to create a unified aesthetic that would be spiritually uplifting to people of all classes.” (Collector’s Weekly)

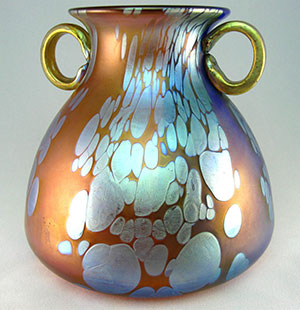

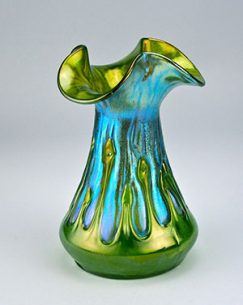

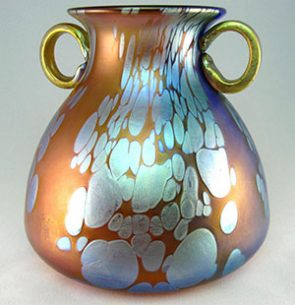

Glass—that material which results from the convergence of earth, fire, and the human hand and which is used by us all in the most common and practical of ways—presented the perfect medium through which the fundaments of Art Nouveau could be expressed, a fact which the glassmakers of Bohemia embraced and perfected, creating pieces that were “hand-worked and sometimes deformed into swirling, organic-looking shapes like seashells, flowers, and tree trunks.” (Collector’s Weekly)

Glass—that material which results from the convergence of earth, fire, and the human hand and which is used by us all in the most common and practical of ways—presented the perfect medium through which the fundaments of Art Nouveau could be expressed, a fact which the glassmakers of Bohemia embraced and perfected, creating pieces that were “hand-worked and sometimes deformed into swirling, organic-looking shapes like seashells, flowers, and tree trunks.” (Collector’s Weekly)

Out of all of these manufacturers, Loetz was the premier, and the progenitor of the Bohemian Art Nouveau style of art glass, inspiring other renowned glassmakers in the region like Kralik and Rindskopf.

Out of all of these manufacturers, Loetz was the premier, and the progenitor of the Bohemian Art Nouveau style of art glass, inspiring other renowned glassmakers in the region like Kralik and Rindskopf.

Loetz was founded in 1836 when Johann Eisner established a glassworks in the southern Bohemian town of Klostermühle (modern day Klášterský Mlýn). After his passing, the Loetz glassworks were purchased by Martin Schmid (in 1849), and two years later, he sold it to Frank Gerstner and his wife, Susanne, who was the widow of a man by the name of Johann Loetz, a glassmaker.

Susanne became the sole owner of the glassworks in 1855, renaming it ‘Johann Loetz Witwe’, and under her direction, the Loetz Glass company expanded and flourished, manufacturing mainly crystal, overlay, and painted glass. Eventually, in 1879, the elderly Susanne passed the company on to her grandson, Maximilian von Spaun.

Susanne became the sole owner of the glassworks in 1855, renaming it ‘Johann Loetz Witwe’, and under her direction, the Loetz Glass company expanded and flourished, manufacturing mainly crystal, overlay, and painted glass. Eventually, in 1879, the elderly Susanne passed the company on to her grandson, Maximilian von Spaun.

Von Spaun immediately set about doing his industrious grandmother proud; he hired Eduard Prochaska and, with his aid, modernised the factory and introduced new, patented techniques and processes. The two creative young men soon pioneered and produced Intarsia and Octopus glass, as well as the very popular marbled (“marmorisierte”) Loetz glass, which was intended to mimic the beauty and colour of semi-precious stones (notably red chalcedony, onyx, and malachite). It was not long before these innovations drew attention and acclaim; Loetz Witwe experienced great success at exhibitions in Brussels, Munich, and Vienna, before going on to receive awards at the Paris World’s Exposition in 1889.

Then, in 1897, von Spaun got his first glimpse of Tiffany Favrile glass, which was being exhibited in Bohemia and Vienna at the time. He fell in instant love with the Art Nouveau style, and the rest, as they say, is history. Over the next eight years, Loetz reached its zenith, both artistically and in terms of profits.

Then, in 1897, von Spaun got his first glimpse of Tiffany Favrile glass, which was being exhibited in Bohemia and Vienna at the time. He fell in instant love with the Art Nouveau style, and the rest, as they say, is history. Over the next eight years, Loetz reached its zenith, both artistically and in terms of profits.

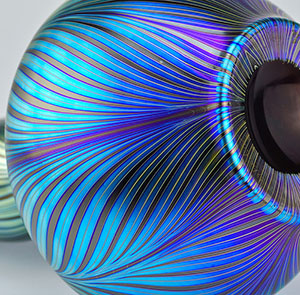

Following von Spaun’s aforementioned inspiration, Loetz produced a great wealth of new designs, largely featuring iridescent, trailing Art Nouveau glass. Loetz collaborated with well-known artists and designers of the era, such as Marie Kirschner and Franz Hofstötter, birthing some of the company’s most iconic pieces, such as the Phänomen series of designs (designed largely by Hofstötter), which won a Grand Prix at the Paris World Exposition in 1900.

Prochaska’s technical expertise and von Spaun’s business sense were so complementary and resulted in so much success (both commercially and artistically) that, for a time, Loetz seemed unstoppable—but alas, even giants may tumble. As Art Deco began to replace Art Nouveau as the most popular aesthetic for art and design, interest in Loetz’s distinct style waned. In-house innovation began to dip, and while von Spaun tried to compensate by increasing collaboration work with Viennese designers, when (in 1909) he transferred management of the Loetz glassworks to his son, Maximilian Robert, the company began to slide into abrupt decline. Just two years later, Loetz Witwe declared bankruptcy.

Prochaska’s technical expertise and von Spaun’s business sense were so complementary and resulted in so much success (both commercially and artistically) that, for a time, Loetz seemed unstoppable—but alas, even giants may tumble. As Art Deco began to replace Art Nouveau as the most popular aesthetic for art and design, interest in Loetz’s distinct style waned. In-house innovation began to dip, and while von Spaun tried to compensate by increasing collaboration work with Viennese designers, when (in 1909) he transferred management of the Loetz glassworks to his son, Maximilian Robert, the company began to slide into abrupt decline. Just two years later, Loetz Witwe declared bankruptcy.

From then on, the dying business was propped up with Loetz family money and the frantic efforts of Prochaska, who introduced etched designs by Hoffmann, Hans Bolek, and Carl Witzmann, plus the beautiful new Tango style of glass (shown at the Deutsche Werkbund exhibition in 1914).

Sadly, a major fire at the Loetz Glassworks coincided with the outbreak of World War 1, compounding the company’s troubles. Loetz never truly recovered, despite the popularity of the coloured opal glass it produced after the war had ended. Loetz recycled its old ideas for lack of fresh new inspiration, until the Great Depression and yet another fire pummelling the limping company into the ground. Tragically, the once-proud and distinctly Bohemian glassworks were seized by the Germans during World War 2 and forced to produce utilitarian glassware for the Third Reich throughout the war. Following this final degradation, Loetz Witwe closed its doors for the last time in 1947.

Sadly, a major fire at the Loetz Glassworks coincided with the outbreak of World War 1, compounding the company’s troubles. Loetz never truly recovered, despite the popularity of the coloured opal glass it produced after the war had ended. Loetz recycled its old ideas for lack of fresh new inspiration, until the Great Depression and yet another fire pummelling the limping company into the ground. Tragically, the once-proud and distinctly Bohemian glassworks were seized by the Germans during World War 2 and forced to produce utilitarian glassware for the Third Reich throughout the war. Following this final degradation, Loetz Witwe closed its doors for the last time in 1947.

Thankfully, Loetz was never forgotten, and is today a legend in the world of glassmaking, one that has gone on to inspire a new generation of traditional Czech glass artists, such as the remarkably innovative Daniel Stepanek. While Loetz itself is no longer with us, the techniques it pioneered are still seeding beauty into brave new designs, into perfect wonders of fine combing and vivid metallic lustre.

All pictures are copyrighted by Loetz.com. There are many more stunning images of Loetz art glass there, and visiting the site is a must for true Loetz fans.